everyday cinema

Foreward:

The Extraordinary Event of Everyday Cinema: On the Films of Marc Lafia by Daniel Coffeen

To me, the most conspicuous and intriguing thing about watching a Marc Lafia film is that it’s clearly up to something. This is a different kind of cinema. Even the ways in which it challenges are not familiar. Sure, the films are generous, exuberant, and beautiful—but at the same time, they ask strange things of us.

And yet what makes them so odd is precisely their everydayness, their thorough engagement with the tools and means we all know so well—only we don’t expect them in our “movies.” There’s something uncanny going on here.

We watch videos all day on YouTube, Facebook, Vine, Vimeo. The recorded moving image has shifted from over there, up on the big screen, to right here, in front of me, at all times. Recording has become ubiquitous, networked, and computational. And yet our cinema remains, for the most part, univocal and monumental. Films today may include ubiquitous recording as something to represent—think of the Jason Bourne films or Catfish—but those films themselves remain monumental rather than computational and networked.

The always-on recording of the social Web is fundamentally changing our way of standing toward the image, toward ourselves, toward each other. And yet when it comes to watching “movies,” we have very different expectations—not just in terms of craft or quality but in terms of what counts as real, as scene, as screen, as filmic event.

As a trained filmmaker who once made feature films, Lafia has no doubt been afforded new methods and undeniable freedoms by new media. He doesn’t need six truckloads of booms, cables, and grips—not to mention a truckload of money. He has an idea; puts together a cast; and films wherever he is—usually the streets of New York. Often, he has actors film themselves on their own, armed with some kind of instructions and a small HD camera. His process is open yet exact, somewhat “scripted,” always developing, adjusting to circumstance.

But this is not an inexpensive way to make a so-called indie film with quirky characters and redemption narratives. This is not a way to make a film on the cheap and avoid the Hollywood scramble for money. For Lafia, new media means new ways of going. In the words of Deleuze and Guattari, new media offer a line of flight from the state apparatus of the film industry. The everyday tools of cinema breed a different kind of cinema, with different narrative strategies, different notions of character, a different interplay of ideas, scene, and even screen. Lafia’s films do not as much use or embrace new media as they are of this everyday cinema. This is not simply a new way of recording: it is a recoding—of cinema, of narrative, of self, of life.

I want to call his films a cinema of emergence, a cinema of the event, in which the very act of ubiquitous recording creates something new. The camera in this digital age—and in the hands of Lafia—is not a means of mediating an encounter or representing reality. On the contrary, the camera is constitutive of the encounter. It doesn’t just record something else happening over there; it forges events in which it is a player right here.

“Hi How Are You Guest 10479” explicitly takes on the always-on camera of the social Web as we watch a woman alone her in Manhattan apartment seek intimacy and connection through adult chat rooms. At some point, it occurs to the viewer that there’s no cameraman there. The incredible Raimonda Skeryte is not just the actor: she sets the scene and records herself—an elaborate Instagram selfie.

This is the condition of cinema today: we are all actors, filmmakers, editors, producers, and distributors. As we are all folded into the cinematic event, what is real and what is fiction becomes irrelevant—not because the recording and the flesh are the same but because the recording is real, too. The camera doesn’t capture action that’s been scripted elsewhere; it’s not an illustrated storybook. As we all relentlessly record ourselves and are recorded, we become part of the cinematic fabric of life, the spectacle of which we are both constituent and constitutive.

These conditions demand a new mode of film. The contemporary French philosopher François Laruelle writes of “the necessity of addressing immanence via immanence in an immanent manner, not allowing for an all seeing purview. . . .” And that is precisely what Lafia gives us: films of the cinematic everyday using methods of the cinematic everyday. Here, there is no outside the gaze, no all-seeing director behind the camera, no fourth wall. If monumental cinema stands back and films what’s over there, Lafia’s everyday cinema flourishes within the infinite web of lenses and screens, within the relentless event of recording—not as his subject matter per se but as his formal approach.

“Hi How Are You Guest 10479” is not a recording of the event of social media—as if Lafia were trying to put a finger on the pulse of the kids today. This is not old media capturing new media. What Lafia does is operate within the world of the always-on camera, the camera that we first read about in Bergson’s Matter and Memory and which, with the rise of the digital, became externalized: from our heads to the world and then, as Debord notes, back again.

No, Lafia’s films are not about this new world order. They are of this new world order, of the always recorded, always played back world: of everyday cinema.

Take Revolution of Everyday Life. The title, taken from the English translation of Raoul Vaneigem’s situationist tome, declares that we’re operating in a place of the spectacle, within that place in which we are always already recorded and played back, run through, not just with images, but with gazes both virtual and real, digital and flesh.

This film, which becomes part of a trilogy along with Hi Guest and Paradise, moves through the streets of New York with intensity and intimacy. Thematically, it seems to be outdated—a radical performance artist trying to foment revolution with her S&M events. It feels very twentieth century. But that, alas, is not what this film reckons.

What Revolution of Everyday Life gives us is different modes of standing toward the everyday camera, a kind of ethics of the always-on camera. Once again, we have the incredible Raimonda, who welcomes the gaze not as a narcissist or even a friend but as a cohabiter, a companion. And we have her lover, played by Tjasa Ferme, fierce and brazenly sexual, demanding attention. Where one stands back and lets the camera roll, the other leans in, demanding the camera’s gaze at all times.

Meanwhile, we get these small, beautiful moments in which other actors film themselves alone—with Lafia’s open-ended instructions—telling these fantastically intimate details. But to whom? It’s not the audience but the camera and its virtual eye, its possible eyes, its infinite eyes. With this film, Lafia tells us that this is the site of revolution: it is in the everyday and how we stand toward the ubiquitous recording event.

Making films of new media means being part of computation and the network. Which, for Lafia, means the screen need not be singular or univocal. In the incredible Permutations, Lafia proliferates the screen, creating a distinct viewing experience that is blissfully hallucinatory. Each permutation is made of short films all shot on the same day and then arranged on the grid of the screen in ever-different arrays. The multiplicity of screens, or of the desktop, in everyday life, has become the multiplicity of screens in cinema.

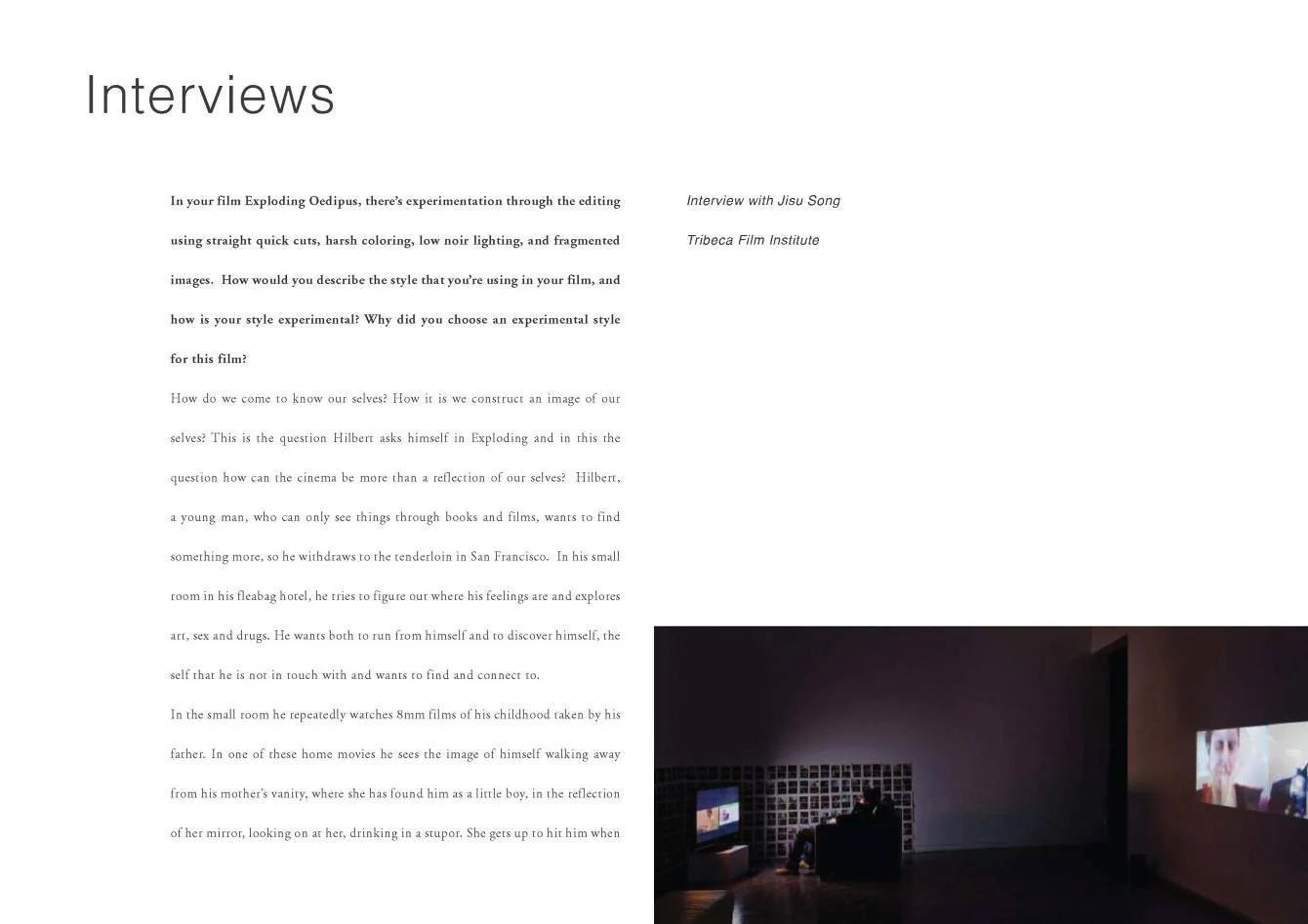

The first film of Lafia’s I saw was Exploding Oedipus, a feature film, which showed at a festival on the huge Castro Theatre screen in San Francisco. Besides being gorgeous, what strikes me now about that film is that the main character, Hilbert, carries around with him a film projector and reels of film taken when he was a child. Which is to say, Lafia has always wanted to put film in his pocket, to project it on the wall, to move it from the outside to the inside, from the over there to right here, from the monument to the intimate.

The cinema of the right here, of the everyday, involves a shift in the economy of the screen, the scene, the story, the character, and the affective experience. This is what makes watching Lafia’s films so uncanny: they operate in a functional and affective space that is at once known and unknown, everyday and extraordinary, familiar and unfamiliar. There are threads of story but his films operate more like social media, a smattering of moments, of posts, woven together to forge this experience. Characters and actors blur into each other without fanfare and pretense; this is simply the condition of everyday cinema. And the affect is intimate, at times uncomfortably so—intense, inchoate, confrontational.

With the rise of the digital, cinema is no longer monumental. Despite the best efforts of Hollywood, making a film no longer demands millions of dollars, booms, grips, lights, and cameras. We don’t need theaters. We don’t need studios. All we need is a mobile phone. Cinema has become everyday. What was once over there is now here, there, and everywhere.

But Lafia is not content with social media as substitute or replacement for cinema. Watching Exploding Oedipus in a grand theater and then, a few years later, watching his Confessions of an Image screened in a San Francisco loft apartment, and then all the others on my desktop, streaming via Vimeo, one thing is glaringly clear: Lafia knows, and Lafia loves, movies.

New media do not signal the end of cinema, as some maintain. Watching Lafia’s films over the years, watching him wrestle and negotiate and explore and discover different forms, different expressions, it seems to me that cinema is just getting going. What I term the extraordinary event of everyday cinema is not the end of cinema. It’s a rebirth. Watching Lafia’s films, I don’t leave thinking: Cinema’s dead! On the contrary, I find myself exuberant: Cinema here! Cinema there! Cinema everywhere!

Lafia is not ringing the death knell of film. On the contrary, I see him as seeking to rescue cinema from itself. As Hollywood closes in on itself with desperately grander and grander special effects, Lafia sees open doors all around. Why are you doing all that, he asks, when all this is right here for the taking? Look! Screens are everywhere! Cameras are everywhere! We’ve created the infrastructure of cinema everywhere! Lafia’s films don’t mark the abandonment of cinema; this is its loving, passionate resurrection.

This everydayness of our social media creates a pervasive recording environment that is very much alive. Recording and screening are always right next to us, with us all the time. It is continuous—with itself as well as with the so-called real. We act now as though a camera were always present because, alas, a camera always is present. Lafia is tapping into the vast, living, breathing cinematic organism that our world has become. We live in a cinematic experience that is always already happening.

And, for Lafia, this introduces new possibilities of film. A hard and fast story line rarely prevails. Rather, all sorts of things happen that are unexpected and unpredictable. Everyday cinema is more like a conversation than a story. We don’t need that old standby, the suspension of disbelief. All we have to do is go with the flow of images, a flow that happens on multiple screens and in multiple times simultaneously. If cinema has always told us stories about ourselves, inflected how we imagine ourselves, this new cinema offers new kinds of stories, new ways of imagining ourselves, new modes of perception and relating, ones that are vital and relevant to the now.

In this book, we see Lafia take up cinema—its history, its grandeur, its rules—and apply the conditions of this new, ubiquitous, always-on recording world in order to forge and proffer something new, something relevant, something beautiful: a cinema of the everyday that is anything but everyday. A cinema that is extraordinary.

There is much to be learned from Lafia’s methodologies, his ideas, as well as from the kinds of reception his films have garnered. Obviously, after Exploding Oedipus, his filmmaking has operated outside what can even be recognized by the festival circuit. He speaks a different dialect of cinema.. Screenings have tended to be discrete events at local theaters. select museums and galleries and for those not local, from desktop to flat screen, thanks to Apple AirPlay.

This new cinema—what I call everyday cinema, but there may very well be a better name—still needs to be fleshed out. I see Lafia as neither an exception nor an institutional leader: he’s an explorer and, lucky for us, at once a theorist and a practitioner. Questions remain: How might we create practices for the distribution of these films? Where can films be screened that are explorative narrative, deeply informed by contemporary cinema, but outside the festival or star system (either of actors or directors) And then there is the question of the limits and possibilities of multiscreen films?, What is the role of public viewing—a beautiful and important experience, for sure? What are the economics of such a practice?

But there will probably be no definitive answers. The computational is essentially plastic and the network is, well, decentered. Hard and fast structures such as studios and theaters are not the defining constructs of this cinematic experience. This new cinema is a cinema of questions, beginning with these relentless questions: What is cinema? How do we stand toward the camera? How do we go with images? There may very well be as many answers as there are films.