making sense

When the curators of the 1GAP Gallery — at Grand Army Plaza, the glass and steel Richard Meier building on Prospect Park in Brooklyn — agreed to show my work, I wondered how we’d come to arrange it, to display it. I imagined its vast glass walls lined with textures and fabrics, the space not just inhabited but ravaged by the work, this work that has a will to bleed. And that would no doubt be glorious.

The 1GAP gallery is interesting in that it moves through, a residential building occupied by owners and paying tenants, many of them with kids. And it's curated as a gallery that is, lest we forget, a seller of art. Both factors — residents with kids and objects to sell — call for a certain discretion.

At my studio inside in the three rooms of the parlor floor of my 125 yr old brownstone, there is no clarity as to what constitutes a work. Works are not discrete experiences; it is an experience of ever-shifting relationships. The works are not framed, arranged precisely to facilitate seeing, one work after another, neatly along a wall or floor to be taken in one at a time. No, the works in the studio bleed into each other, become tableaux of assemblages, where anywhere you look a work enjoins another, inflects another, combines with and contagions another - what is on a wire suspended in the middle of the room comes into the color filtered light of a work hanging over a large window with tubes that run into a floor object which connects to a mannequin continuing alone the floor onto a silk covered drum kit - each making new sense of something else. The work I had been doing is not a series of discrete works. Nor does any one piece have a definitive way to display itself.

So how then would the lived-in 1GAP arrange and set about showing this ensemble of work as something discrete. How was the gallery, going to turn the work into "art" — into an institutional commodity, framed and poised for consumption. This institution is more than the gallery; it is the history of art, an engine of capital, academia, publishing, museums, collectors. Duchamps' Fountain only works because there is such a thing, an institution that is as much transactional (for buyers as well as viewers) as it is ideological and spatial. The curator in this case, Suzy Spence, had the difficult task of turning my viral, schizophrenic work into something ‘respectable’ and readily consumable. She did that by choosing work for the windows, work to be seen on its own, work that has something to say within the discourse that is institutional art.

In his his essay, ‘Schizo Sense: On the Space, Place, and Drape of the Image in Marc Lafia's "Making Sense"', much of which I adapt here, Daniel Coffeen writes

‘Unlike most people who will see this show, I've had the luxury of experiencing it in the two venues. And this affords me a distinct pleasure: I was able see this body without organs, as Deleuze would call it, become a presentable organism — a shapeless, shifting morass of color, texture, and affect become a refined yet witty conversationalist. And so now I see it in both states at the same time, a body that keeps shifting its posture in such fundamental ways while somehow remaining recognizable. Back and forth this work goes, always becoming, always becoming other to itself in the very act of its actualization.’

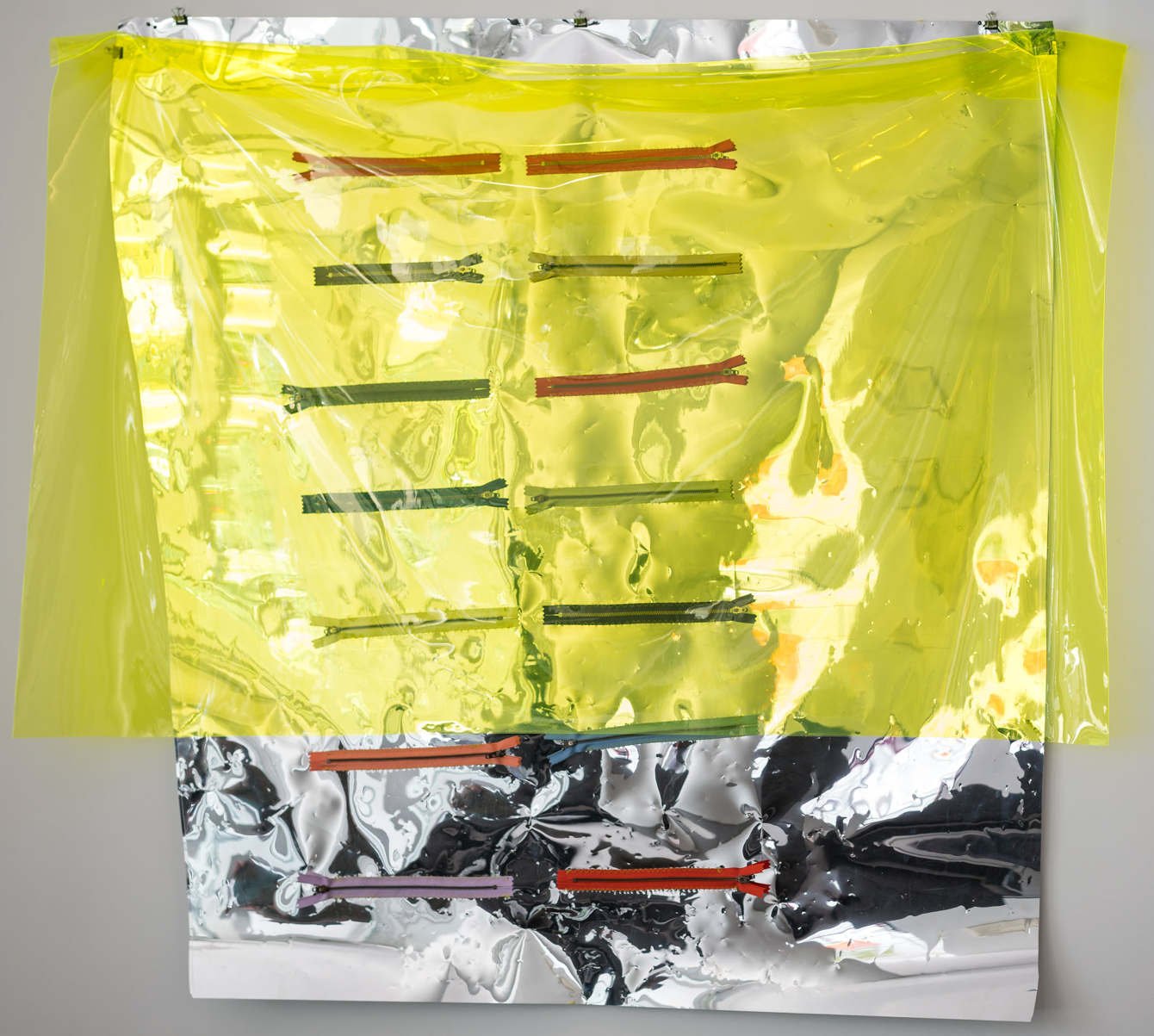

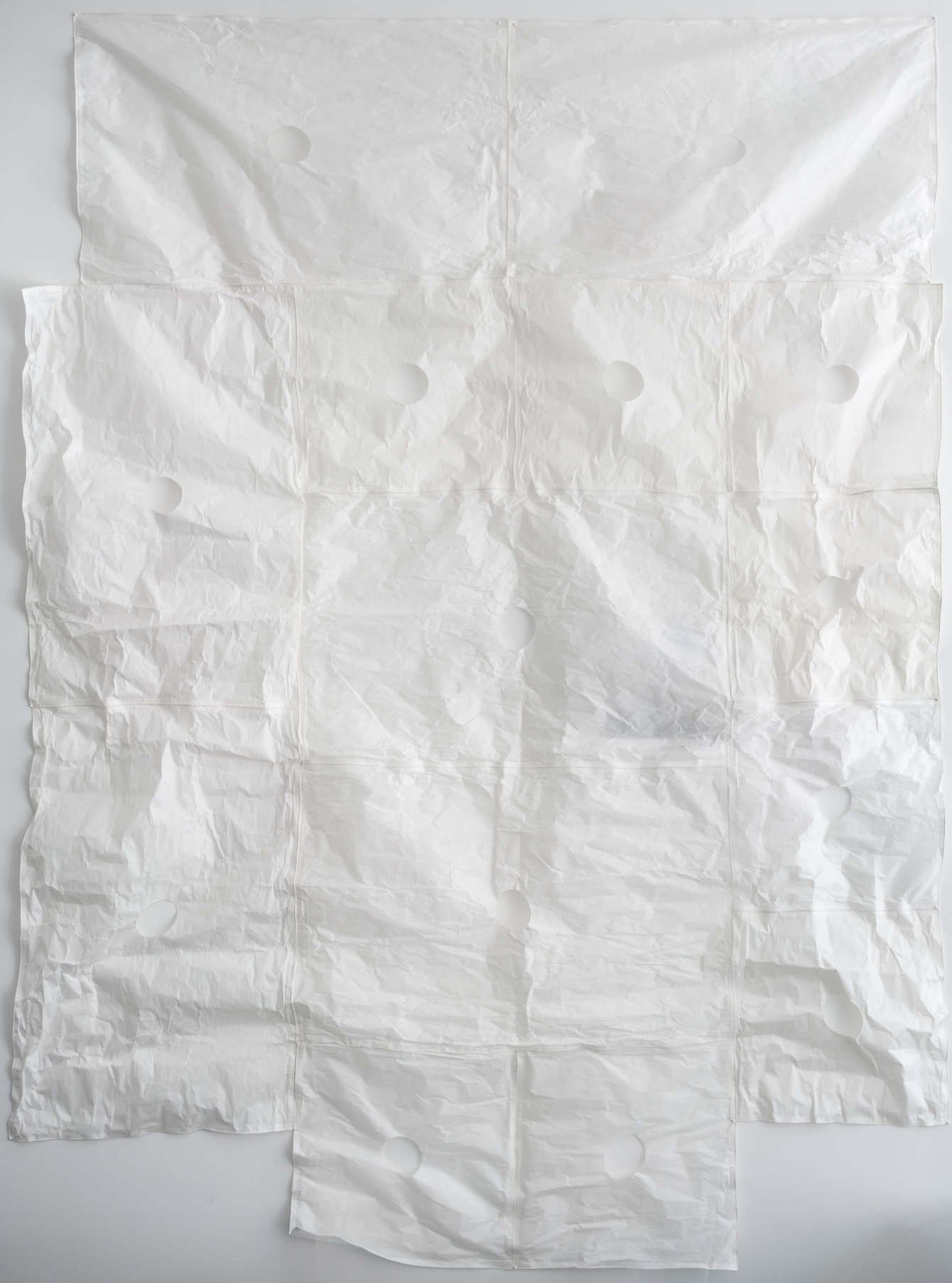

When asked to describe this new work I begin by talking about how I set about it looking for a new material substrate to print images on. I wanted something that had a knowing sense of its object hood. Not simply a framed paper or aluminum print picture but a picture that knows and performs itself as an object as a thing. In time I come upon the idea of sewing together the thin articulable wire framed sheets that make up Ikea paper lamps. I would sew them into large sheets, 10 or 12 feet by 8 feet. Several things happened, one, the typology of the sheets with their rolling kneaded surface required to be put through a special printer, which becomes expensive and two the sewn sheets wanted to be something entirely to themselves. I found them very beautiful, blank. In that ‘blank’ in the whiteness there was an eternity. I then move onto plastic, sewing plastic, first patented as celluloid in 1869. Recall that at the end of the nineteenth century George Eastman introduced transparent flexible film, made from cellulose, making the highly specialized trade of photography into an everyday affair for the general public. As we know, the plastic substrate of film becomes obsolete with the advance of the digital. Transparent plastic, once the material that captured recorded light, as a negative in film cameras, assembled and sewn was now an object in its own right, reflecting the ambience of light, the surface qualities of various material densities continually recording and being.

This then became the prompt of this new work, the desire to touch the substrate of light, to make something that sculpts light and color, that moves across the vast spectrum between light and dark, that suggests and invites, and simply is. As the great French phenomenologist Maurice Merleau-Ponty argued, all vision is palpation. When we see the world, says Merleau-Ponty, we touch the world: we bring it to our bodies just as we go to it. Here sight and touch are entwined and, at times, even interchangeable. In this intersection of vision and of touch, of textures and colors, the work increasingly took this material turn, opening up further and further the tactility and presence of things, here and now, things not pointing to an elsewhere, as images often do, but things that say Here I am.

This moment from image to thing, this haptic experience Merleau-Ponty would call this a chiasm, an intertwining, articulated in the middle voice — neither active nor passive, both active and passive - lead me further into this exchange with material history and its shaping by visual artists from the first readymades presenting things as such to assemblage, putting various fragments together, in order to compose a piece, to combines and 3d objects and installation.

At first glance, it could be said that assemblage is a three-dimensional alternative to collage – a technique of composing a work of art by pasting on a surface various materials not normally associated with one another. The term was first introduced to the art world by Jean Dubuffet in the 1950s. Still, the genesis of assemblage owes a lot to the introduction of a ready-made, which made it possible for everyday objects to participate in the creation of art projects, once again pointing to Marcel Duchamp. But what role does assemblage play now, in the Post-Internet era?

There is in this, post digital, a turn to the material, not the material of code, but physics things. We see this as a younger generation has returned to vinyl and analogue film, tape recording, printed zines, brewing, cooking and baking. In all materials there is a history, a pedigree, chemistry and fabrication, transport, storage, circulation and commerce. From Gutai, to the Zero Group to Art Povera to Donald Judd and Eve Hesse to Cathy Wilkes and Isa Gengken and Danh Vo, what started out as a desire to find make a print on a new substrate became a immersion into substrates themselves. And then of course, how can both be themselves and something else.