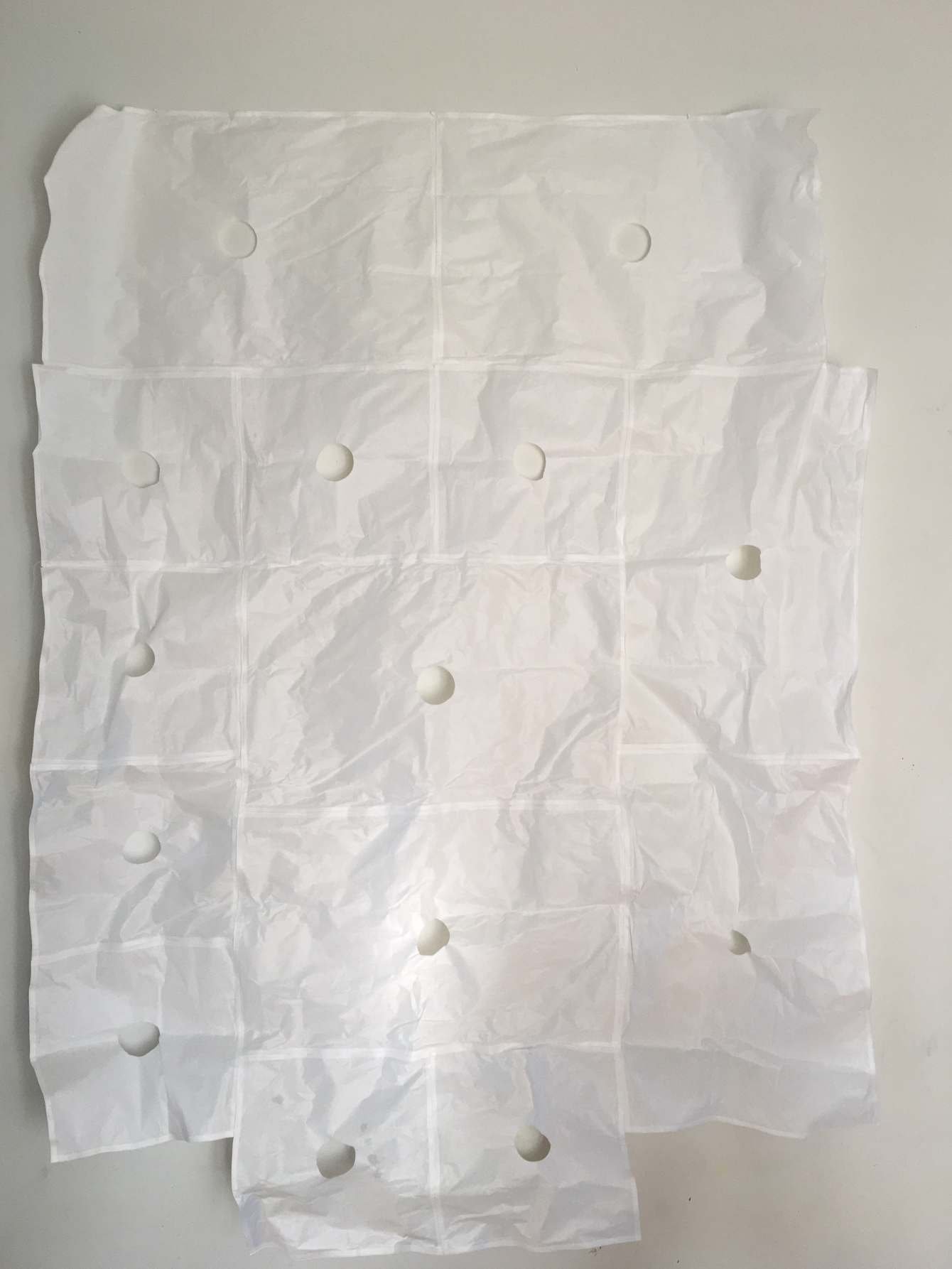

concatenations

Asafir bila Ajniha, Wingless Birds

2017

69" x 92"

lamp paper, white thread

C-print

The Dream of the Fisherman's Wife or This page Intentionally Left Blank

2017

69" x 92"

lamp paper, white thread

That I Should Cease to Be

2017

49" x 24" x 10"

polyester wardrobe, silk, plastic pipe

Things Fall Apart

2017

92" x 54"

Ikea lamp papers, organza, varied plastics transparent, cloth zippers, assorted threads

Antartica

2017

24" x 21" x 16"

wire frame lamp paper, colored plastics, varied threads

This Rare Earth

2017

69" x 92"

lamp paper, white thread

C-print

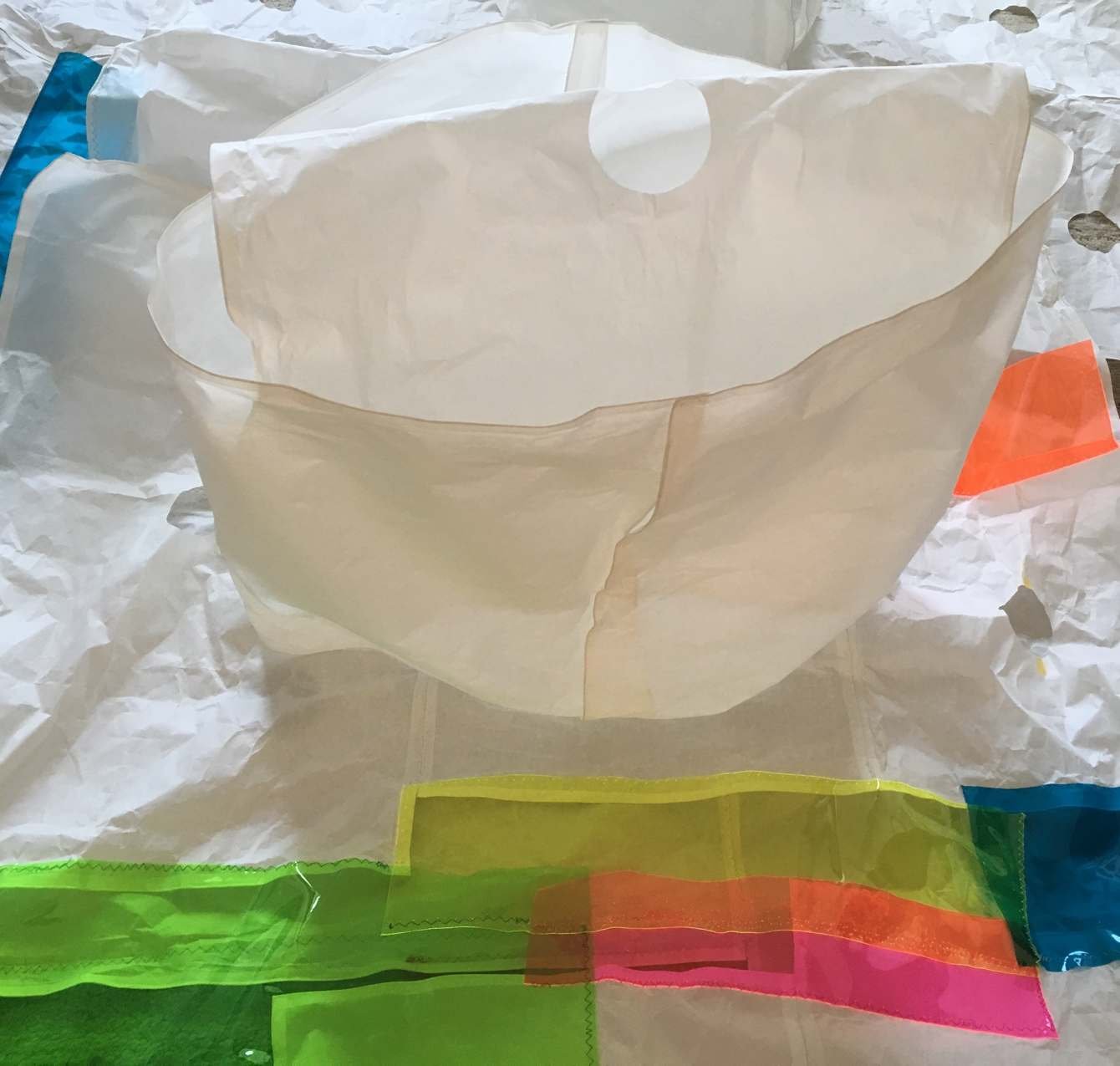

The Sense of Centrality in Every Being That Exist

2017

61" x 57"

ikea lamp paper, transparent plastic, 3d plastic, 4 cloth zippers with brass finish, silk

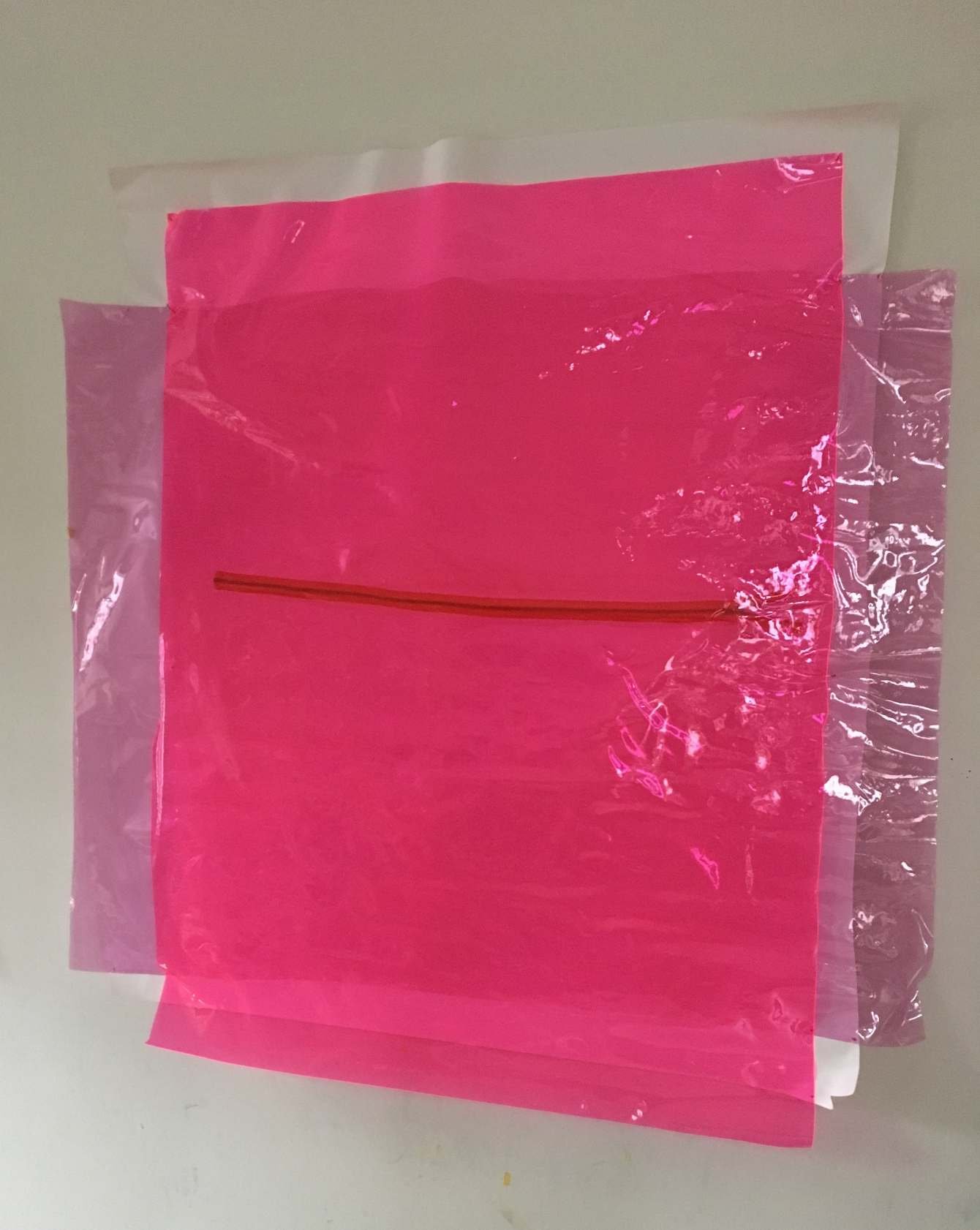

The Rape of Ivana

2017

57" x 38"

gauze, scrim, silk, plastic

Those Who Suffer Love

2017

55" x 17"

latex, lamp paper, tubing, lanyard, assorted threads

Map of the Oceans

2017

97" x 55"

Ikea lamp paper, gauze, silk, mesh, transparent plastic, assorted threads

My Yellow Pill

2017

69" x 92"

lamp paper, white thread

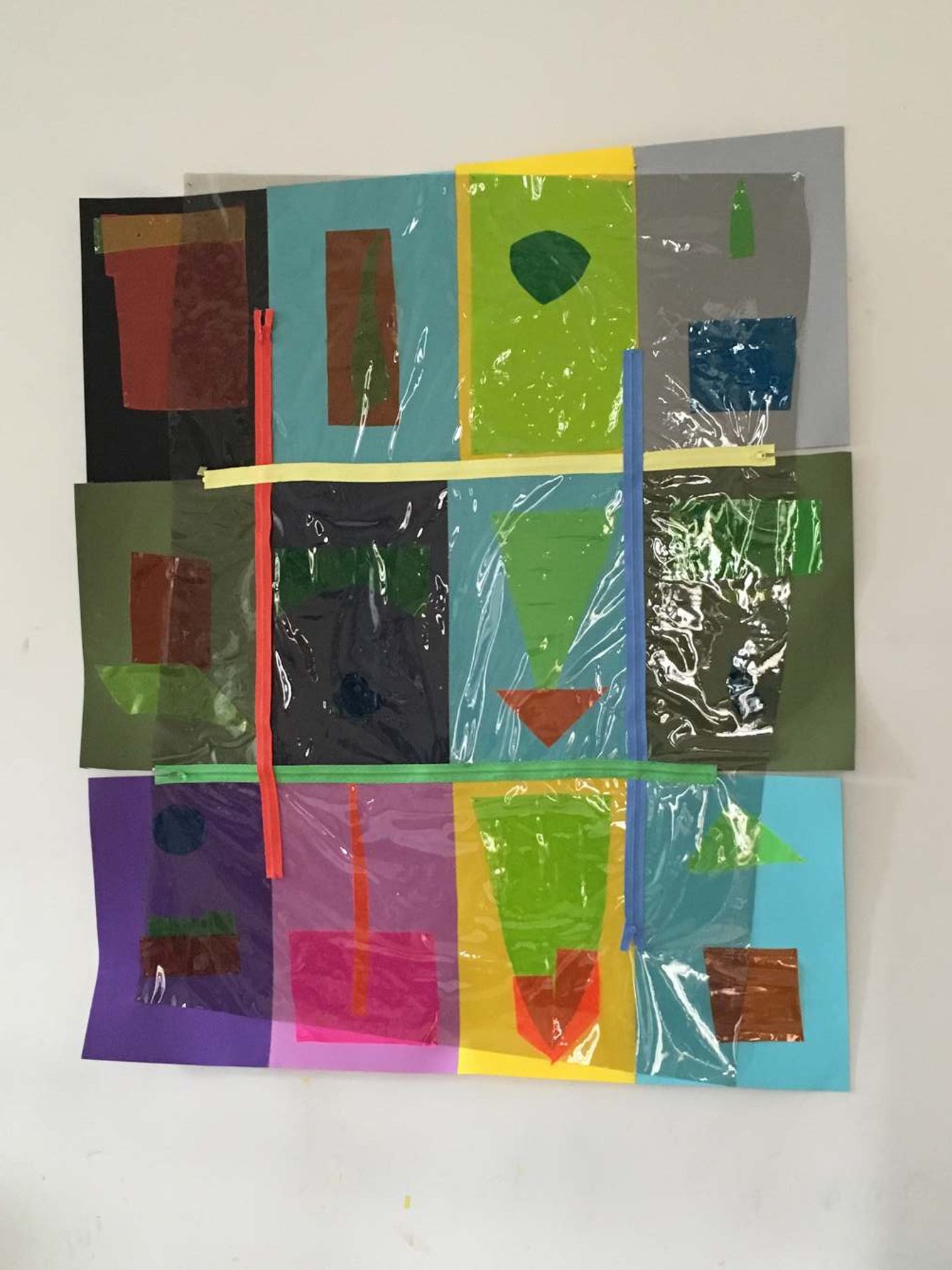

How to Build a Universe That Doesn't Fall Apart Two Days Later

2017

57" x 50"

zippers, colored sheets of foam rubber, colored plastic

Diagram of Wind

2017

105" x 55"

Lamp paper, colored plastics, varied threads

Utopia or All Things Excellent are as Difficult as They are Rare

2017

57" x 54"

white matte plastic, zipper with brass, transparent plastics

Through the Night Softly

2017

64" x 30"

lamp paper, gauze, varied threads

Dream Caused by the Flight of a Bee

2017

38" x 33"

lamp paper, gauze

Between Stars There is Darkness

2017

56" x 54"

lamp paper, neoprene, gauze

The General Intellect is Looking for a Body or Never Remembering Having Gone to Sleep

2017

55" x 24"

polyester wardrobe, latex, gold paper, plastic pipe

I Can Hear You

2017

69" x 92"

lamp paper, white thread

C-print

The Society of Plastic and Paper

2017

66” x 50”

lamp paper, clear plastic, acrylic sheets, varied thread

4.33

2017

42" x 33"

orange acrylic, cellophane, ikea paper lamp

Fountain

2017

53" x 47"

clear plastic, paper lamp, metal stretcher

Diagram of Wind

2017

90" x 66"

lamp paper, organza, synthetic silk

Power, Corruption, Lies

2017

68" x 60"

lamp paper, cloth brass zipper, indian silk, thread

The Glories of This World

2017

120 x 22.5

zippers, lamp paper, transparent plastic, pantone colored paper, gold paper, aluminum, 3d sheet plastic

Planting Flowers to which the Butterflies Come

55" x 77"

Ikea lamp paper, gold paper, wool, varied plastics, zippers with varied finished, assorted threads

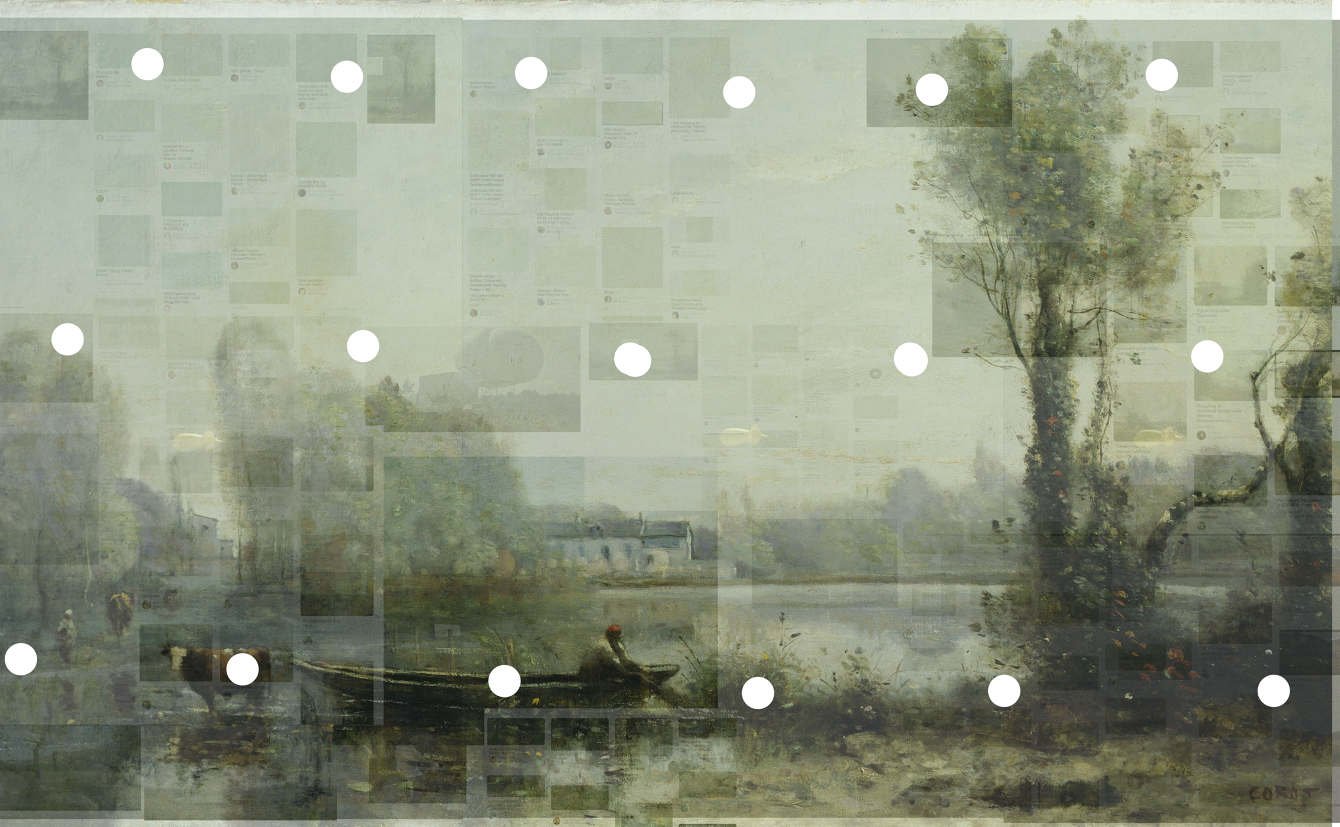

All Watched Over by Corot

105.75" x 66.75"

*Note here in the image you don't see the underlying paper and its typology which it is now being printed on.

“There was a shift in the twentieth century in the meaning of materialism, away from realist depiction to an emphasis on matter itself. So in minimalism one is confronted with the base

materials that make up daily life, like the base materials of the architecture one lives in presented in an unformed state. And what happens is, one becomes strangely body-conscious

in this situation. The focus of the art experience shifts from experiencing an object to experiencing oneself in relation to the object, environmentally. “

Mike Kelley

”Concatenations between conscious and sensitive organisms can happen as conjunctive concatenations and also as connective concatenations. Human beings conjoin thanks to their ability to linguistically and sensuously interact. Sensuousness and sensibility might be said to be the ability of humans to communicate what can not be said in words. (and I would say as images, snapshots or photographs).”

Franco Berardi

”This sharing of duration is automatically defeated by

the innovation of photographic instantaneity, for if the instantaneous image pretends to scientific accuracy in its details, the snapshot's image-freeze or rather image-time-freeze invariably distorts the witness's felt temporality, that time that is the movement of something created. “

Paul Virilio

Concatenations

In this new work I want to make, and not make, image of society’s instruments and substrates of visualization, to see them seeing us, but it’s not us that they see, but simply edges and colors, patterns and hues, likes and clicks, border crossings, credit card transactions, all of it numerical encodings in vast tables of databases. If camera vision and images were once seen and ordered through human agency, they are now seen and retrieved by machines. As such we mustn't look at images as indexical of human affect but of machine processing and ‘seeing’, turning the realm of human sensibility and action into something strangely abject and the human into a very new kind of object. This vast realm of everyday recording, of computerized seeing, sensing, tracking, aggregating and permissioning, makes of us, the messy and emotional, a signal, an index, dissolute and atomized data at a time when we are wont of discourse, sociality and the sensual.

As we transfer authority to the market and data, to our sensors and screens, and the analytics of such information the dominant values of our culture increasingly privilege sight over touch, information over empathy, the cognitive over the sensate, the image over the event. Working principally in the realm of the image, moving image and the society of the network, I want here to engage with the ambience of light, the qualities of touch, the situational and the environment, the materiality of the event of light, plastic, rubber and paper, each with its own tactility. And so there are works here of images of imaging, imagining as instrumental, as multiplicities and at the same time, works whose materials are shaped to take light and place us, the viewer in relation to our bodies sense of touch.

In the age of the Anthropocene, the planet has been become a work of human design, its peoples and habitat something to be managed, monitored and continually observed, all of it in hopes of creating a frictionless and reasoned world. But quite the opposite has happened, ‘the wholly enlightened earth is radiant with triumphant calamity,” as observed by the Frankfurt School.

This new work goes along several tracks, one to image this new condition and the other to dissolve it, to get to a new zero point starting with the very substrate of the image surface. Whereas most photographic images are printed on flat surfaces and are indifferent to the surface, except for the finish, these works start from the very substrate of the print material, a materiality with a life and being of its own. With these new surfaces, new materials, these works are simultaneously ambient and voids and at other times narratives in image. They continually play between image and their erasure, between an image that points elsewhere and a surface that can, in a Bergsonian sense, be considered an image and substance in itself. They are on the one hand light sculptures and the other tableaux.

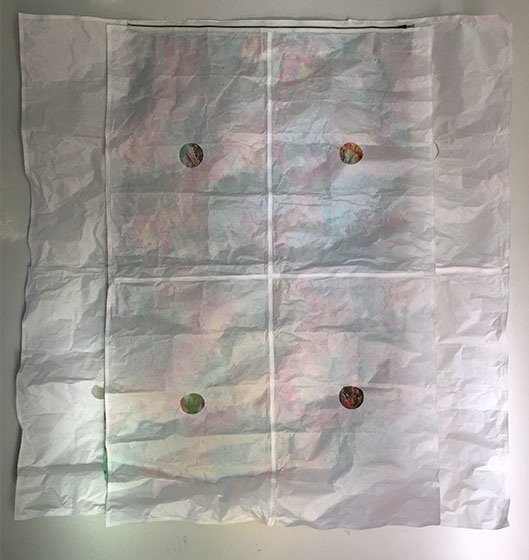

The material substrate of the work have made from the individual sheets of ikea paper lamps, taking the lamp apart and sewing, together, the paper sheets, assembling combinations of squares and rectangles with various stitchings and threads. This material surface has body to it and is shaped and folded to scale up, adding more and more sheets making pieces larger and larger or giving works sculptural volume.

I think of these as plateaus, as geographies and topographies, as shapes and volumes as concatenations of flows. They are very simple and beautiful in and of themselves, in the purity of their uniform all white color, in the wholes in the center of each sheet, in how ambient light reflects on them, in their gentleness and lightness. These works have a certain body to them and are supported by light wire frames built into each sheet, so they can both inside the pieces and on the edges be articulated and shaped. there is no framing, no glass, they fold up to be shipped. They are very smart and ecological in their design and presence.

Where as most prints are on paper or aluminum and set into heavy frames with glass and plexi, these works are easily installed with a few properly placed pins or nails.

Along with the all white paper pieces, there are others with colored sheets of plastic and varied fabrics. these like the instascapes I made years back, play with opacity, transparency and overlay. These play more a game of ratios, of color, of filters, hot and cool, tepid, demure suggesting infographics, geopolitics, dispersal, bling, happiness, how things are stitched together, made of this and that, a kind of gumbo and hazard.

Plastic was first patented as celluloid in 1869. At the end of the century George Eastman introduced transparent flexible film, made from cellulose, making the highly specialized trade of photography into an everyday affair for the general public. In some sense I want to dissolve the photograph back to a state of zero, to the plastic it was first printed on. To bring the digital back to the analog, to bring materiality to the circulation of the digital file, to go back to the earth, to exit the virtual bus and show the stuff of things.

As we know the plastic substrate of film becomes obsolete with the advance of the digital. And if there once was conviction that the photograph, as phenomenologically described by Roland Barthes, as —“This-has-been; for anyone who holds a photograph in his hand, here is a fundamental belief… nothing can undo unless you prove to me that the image is not a photograph.” — then in this work, I turn away from photography and the this-has-been of the image, to the very material that once carried it, plastic. Not only plastic, but materials that advance from it, including latex, rubber, coated papers, sheer fabrics, synthetics, all of them sharing the quality of imaging, capturing light. In a world of ‘alternative facts’ there becomes something substantial, as in substantive with materials. Unlike the photograph and the ‘this-has-been’ in these new works I want to present ‘this is.’ The ‘this is’, is the the desire to touch the substrate of light, to make something that sculpts light and color, that moves from between light and dark, that suggests and invites and simply is.

Like info graphics that distribute information across grids, these works further Ellsworth Kelly’s idea of - transfer - extending the idea to translation. In data science, search algorithms read images, indifferent to what is represented in an image. The info graphic of aggregate data presents an orderly image of a very messy world. But’s it all leaking, melting, falling apart, stitched together, you look here and the world is blue, there, and it’s orange, hot or cold, happy or uncertain, all of it changing with light. Constructed with various papers, fabrics and plastics these pieces are light sculptures, light instruments in there own right. These works (influenced from my time in Japan) have a presence, an ambience, a void, a sense of reset, a quiet and can be considered light sculptures, cameras in themselves.

At the same time, for other works the substrate carries an image, an image of instruments of visualization, our instruments seeing. Here then we move from surface object, to projection, to print narrative. If data society and its visualization is entirely indifferent to the life lived by a subject, it never-the-less creates a new subjectivity. A subject spliced into an enormous technological apparatus, a subject and earth seen and monitored, indexed and parsed into vast transactional and security networks.

If the central emergent feature of modernity was the further development of a rational capacity and at the height of abstraction there was the idea of an ideal, a certain perfection or purity or simplicity, these works reject that and present a materiality that is torn, uncertain, sheared and sewn. According to Heidegger, calculative thinking “races from one prospect to the next. [It] never stops, never collects itself. Calculative thinking is not meditative thinking, not thinking which contemplates the meaning which reigns in everything that is”. For Heidegger the modern world is under the one sided dominance of this type of thinking, and as a result the earth now appears “as an object open to the attacks of calculative thought, attacks that nothing is believed able any longer to resist. The instrumental rationality of Big Data has become a tool used by elite power for imposing order, dominance and control. The future will likely reflect narrow corporate and state visions, rather than the desires of wider society, a society and myself, that wants to become re-embodied, present to the material and ambience of the world.

The work then is both the substrate of image and the image of imaging, of underwater drones, inflatable satellite terminals, machine readings of the surface of landscape painting, probes into rare earth metals, and far away light signals, this is our realm of being seen, but not as a subject, not as a whole thing, but as a threat or an opportunity, this is life in the smart city, where if there is void and ambiance, it’s a managed and consumer pleasure that any moment could have a helicopter flying over it, or drone at your back. Here instrumental reason is the Kool-Aid of sundry courtiers and sycophants of hungry albino alligators. Here there is no substrate, there is only image, a steady drip of horrors and the messy affairs of empire, all of it continually packaged, remixed, re-recorded, and the earth and the heavens a thing to be monitized and exploited. There are no subjects in this new regime of instrumental visioning only correlations and equivalences, markets and machines and we, but nodes in a network, all of us watched over by machines of loving grace.

To give this feeling when we enter the space we see a very large 20x28 feet image on this highly topological paper of a yellow underwater drone and on the other wall an equally big print of an inflatable satellite terminal. In the satellite image we see a layer of deep blue sea above the sky and hanging lower down like shaped small parachutes are substrate images of mauve green insectotopeters (micro surveillance insects). The colors are so extraordinarily beautiful we look up in awe at being looked downed at, observed, surveilled. On the ground there are ambient light sculptures and scrim works of fabric and colored plastic, hanging like large sheets on a laundry line, works that suggest data visualization but hand crafted and walking through, like stain glass give everything in the room a different color inflection, what is and its appearing, whether as natural beauty or as numerical presentation, we not sure. Until we look close the seductive beauty of the install and designed environment does not let us see we’ve been trapped by our reason.

* A specific note on the Corot work, 'All Watched Over by Corot.'

For these new prints I've been working on creating a new print substrate, the substrate is more of a topology than the flat surface we always see prints on. Ordinarily with prints, the material surface, except for the finish, is thought of as a non-thing. We're suppose to see past it, to the image, the print surface is something we aren't really seeing. I want to see this material and I want it to announce itself performatively. I want it to be part and parcel of the image, a body and thought, a substance, in and of itself and part of the image.Something that speaks to seeing and sight but more precisely, touch and sight and different kinds of seeing.

The print sheet is sewn together from paper sheets that come in packages for IKEA paper lamps. I like the idea of the paper being industrial, everyday, and whose purpose is to be a light and in this case the light bulb missing.

Photography is light but today’s image is stored as data. It is impossible to touch data. Machine sight and computational information increasingly eclipses the somatic and empathic, skin and flesh, sight and touch, and the data body politic becomes a biopolitic, an atomized swarm. Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, a harmonist of color, in his paintings, imbues in nature, a beneficence, a beauty, life and grace. To us, this may seem overly romantic, an effusion of pathos. But you can touch his painting and see it. I want to touch the image. I want it to be palpable. I want to feel it, its ripples, folds and contours, its cracks and creaks, its impermanence, its body. Paint does have a body that print doesn't. By rethinking print paper and using this paper that folds and deforms I want bring body to the image and embodied sense to the viewer.

In the image, Corot's landscape painting, Ville-d’Avray (17.2 × 29.3 in) is printed 4 times the size of its original, and is seen overlaid, on top smaller images of the same painting ‘read’ or scanned in sections by Pinterest’s 'visually similar' algorithms, and on top of that a country side landscape being surveilled by an Aerostat blimp equipped with radar that can ‘look’ in 360-degree circles. Corot’s landscape is seen and imagined, (he made many preparatory sketches outdoors on location) by a closely felt and observed world, and environ. He wrote, ‘Beauty in art is truth bathed in an impression received from nature. I am struck upon seeing a certain place. While I strive for conscientious imitation, I yet never for an instant lose the emotion that has taken hold of me.’

In contrast the other two ‘seeings’ in the picture are machine and algorithmic seeing, each transposing what is seen of datasets of billions of pins or other data. In the case of the Pinterest image search, by specifying a part of the image using the cropping tool, one can scan the Corot reproduction, just as the JLens Aerostat scans the landscape, in real time. In both cases, and in ‘search’, ‘exact’, as well as ‘unexpected’ results, along lines of what is similar in style, pattern, shape or coordinates are interpolated and delivered. What fascinates me here is the disjunction between my sense of pattern recognition and the rule sets of these visual engines and what they retrieve along this spectrum of ‘exact’, Machine rules-based seeing and human affective, socially constructed seeing, are of very different orders and registers. They are different patterns or programs of recognition In this picture I want to see each of these ‘seeings’ simultaneously, from the most romantic to the most indifferent, from human to machine, affectively transposed and most of all, not flat. I want my image to be touched, not simply by a flat indifferent surface or a screen, but a body, a topology, ever changing, vulnerable and impermanent.