image photograph

Below is the forward to the book published by Punctum Books

Photography as an Image

(foreward to Image Photograph)

Daniel Coffeen

The opening line of Marc Lafia’s book is fantastic: “Photography as an image.” It’s not a sentence. It doesn’t have the familiar grammar of subject, verb, object. What I love about it is that it’s not the didactic declaration that “Photography is an image.” Something much stranger, and more beautiful, is happening here—something more generous.

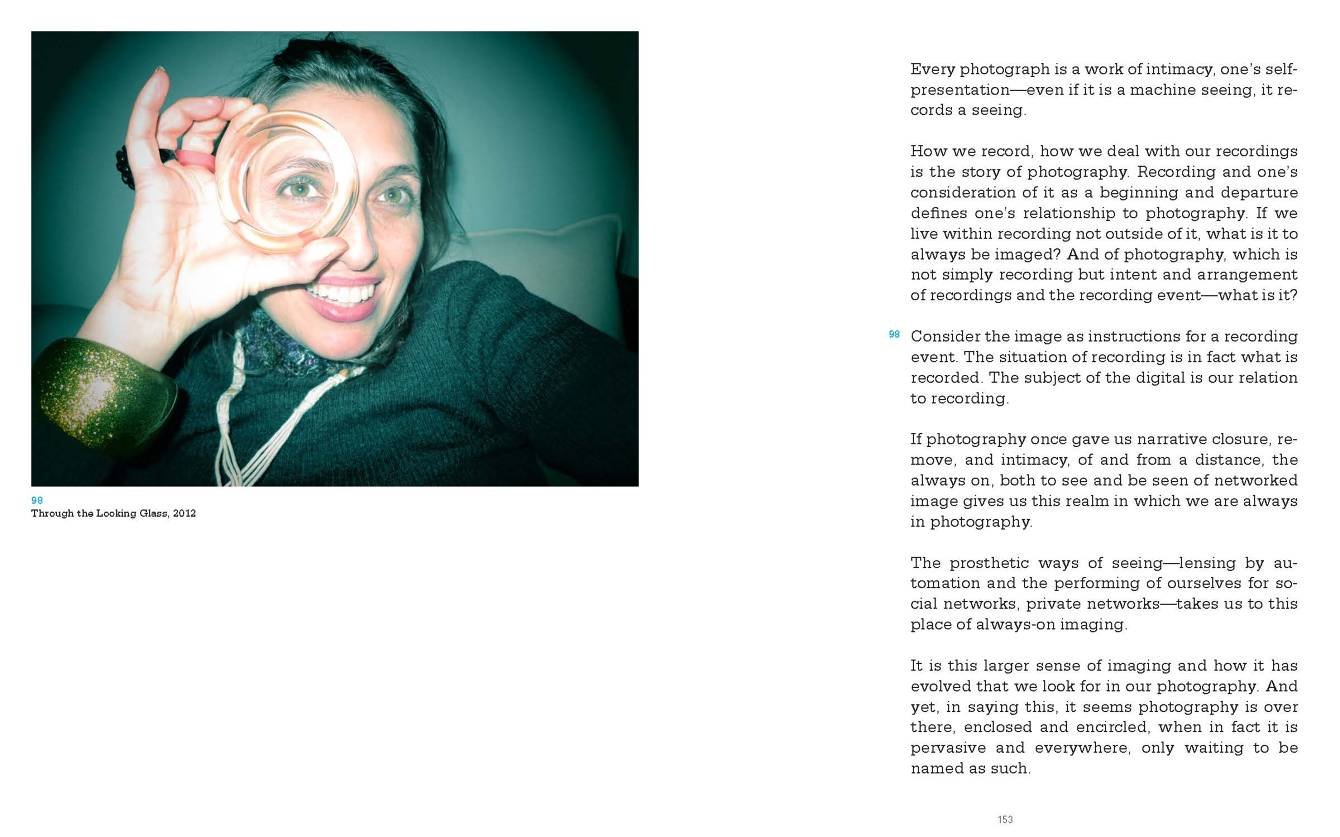

This is how I imagine the scene just before the book opens. The photographer peers through his lens onto the world to find Lafia standing there—looking back! Only Lafia’s not looking over the head of the camera, bypassing the technology to engage the eyes of the photographer. No, Lafia is looking through the looking glass itself. Like the photographer, Lafia sees with the camera, but in reverse. And through the looking glass we go.

When Lafia looks back through the looking glass he doesn’t just swap places with the photographer, the seer becoming the seen (even if that’s a dramatic scene unto itself!). He creates a living circuit as they both become seer and seen, photographer and image, the technology now within the frame, snapping away. It is a relentlessly creative circuit, forever forging more images.

The great French phenomenologist Maurice Merleau-Ponty argues that the very condition of seeing is being seen. We can only see the world—touch the world, know the world—because we are part of that world, continuous with its fabric. Merleau-Ponty calls this flesh. He claims flesh to be an element akin to earth, air, wind, and fire. All things are enmeshed in the flesh of the world. The very conditions of the seer seeing is that he is something that can be seen, that he is part of this flesh.

And that perception, including vision, happens within this flesh. It is not a magical event, a pristine event that bypasses the stuff of the world. Vision is an event that is of the world, that links things together in complex calculi. Vision is what Merleau-Ponty calls a chiasmus, an intertwining, of seer and seen, subject and object. Seeing happens within the world, as part of the world, with the world.

Isn’t this the explicit condition of the digital network? We inscribe and are inscribed in the same breath, our seeing always, in turn, a seen.

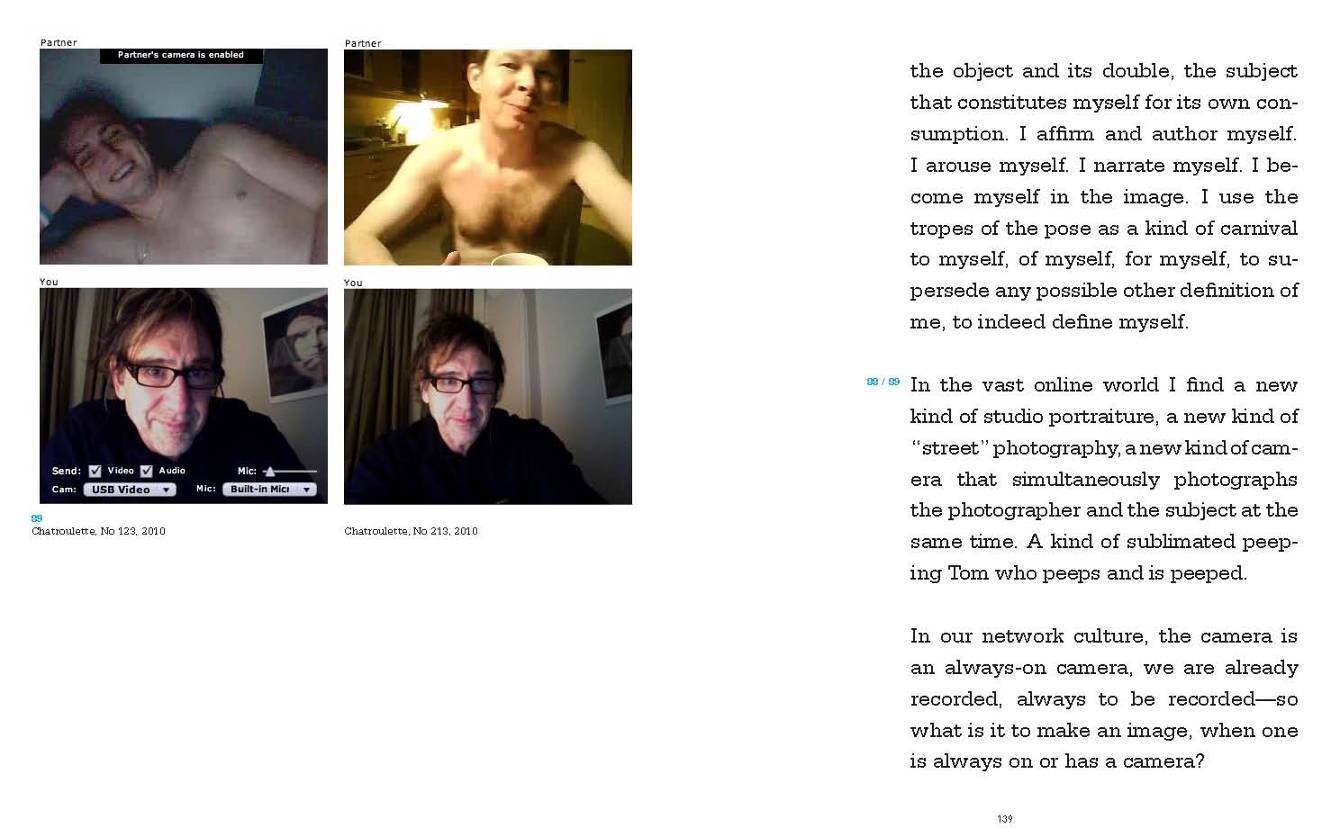

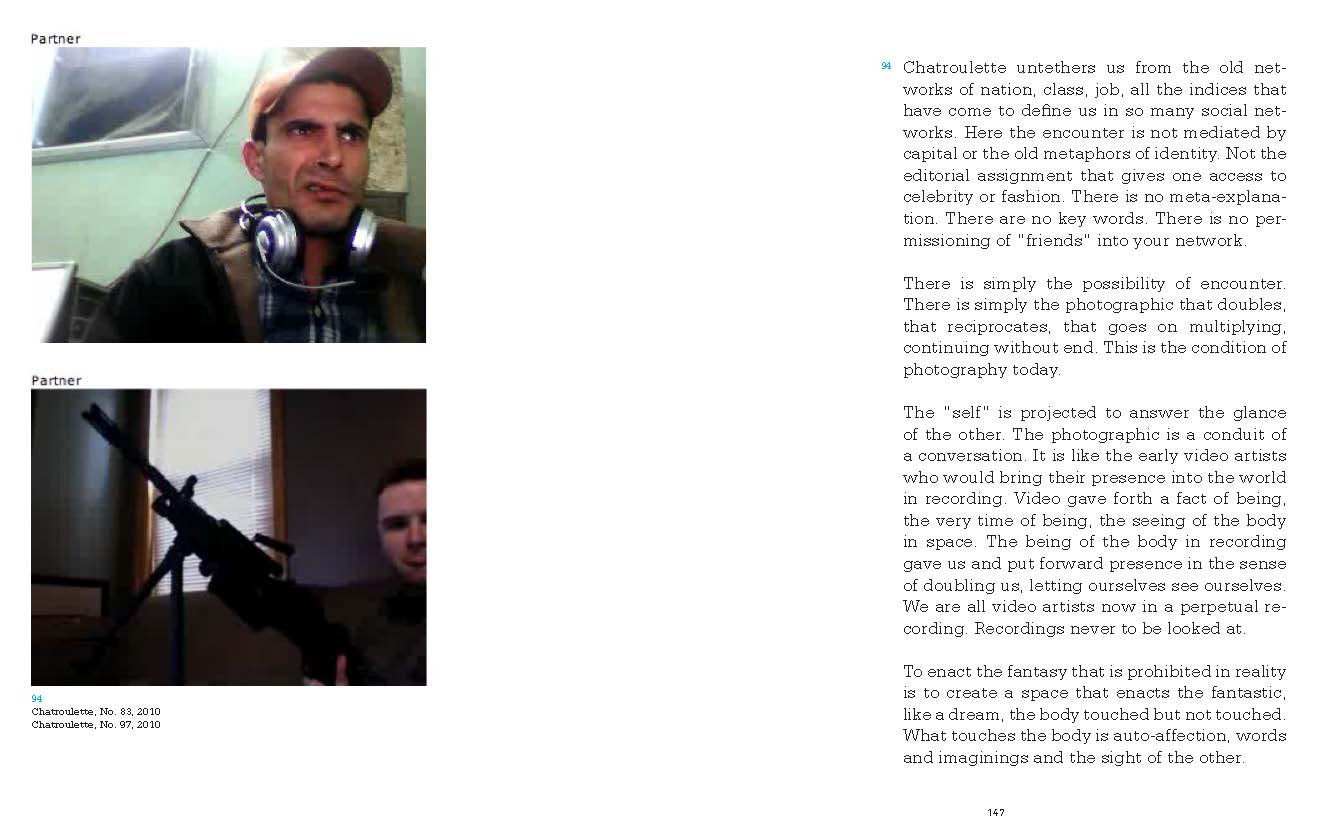

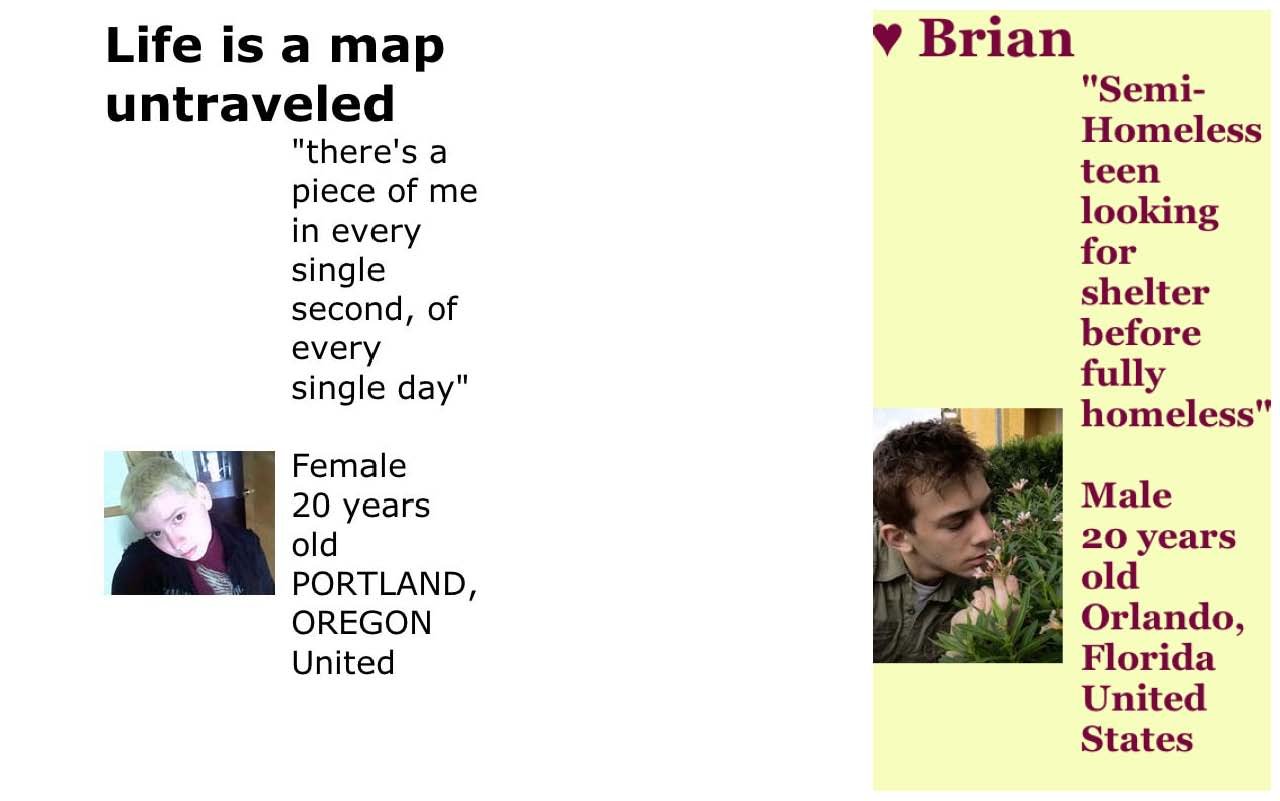

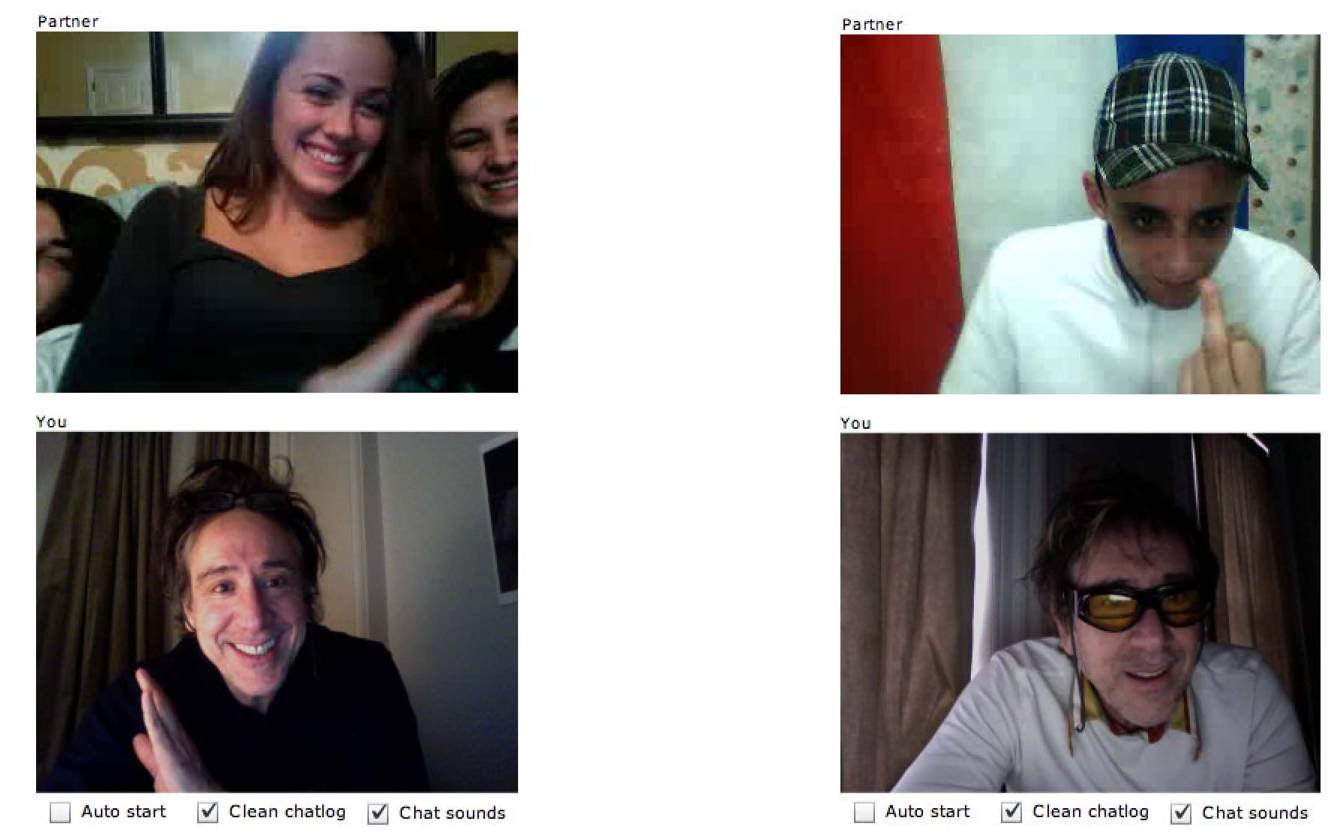

It is not a wild hypothesis to claim that we enjoy a different relationship to the image today. The camera is no longer a specialized tool we use to record special moments. The camera is now always on, simultaneously reading, writing, archiving: the Web, the smart phone, Instagram, surveillance, telemedicine, MRIs, Skype, Chatroulette, ATM cameras, credit card imprints. If before the digital, the camera kept a distance between photographer and world, in the digital network, technology entwines us—and entwines with us. The relationship between body, self, technology, and world has shifted. Il n’y a pas de hors-image. There is no outside the image.

One way of reading Lafia’s book is that he asks the obvious, pressing question: In this world of relentless imaging, what becomes of photography?

Now, Lafia does not give us a ready answer. He can’t. To give a ready answer is to be outside the fray, outside the circuit of seeing, this entwining of bodies and things and perceptions. But Lafia’s book is situated within this fecund, living circuit. And from within, seeks to map a new territory, to articulate the strange and beautiful new relationships between world, technology, image, and us.

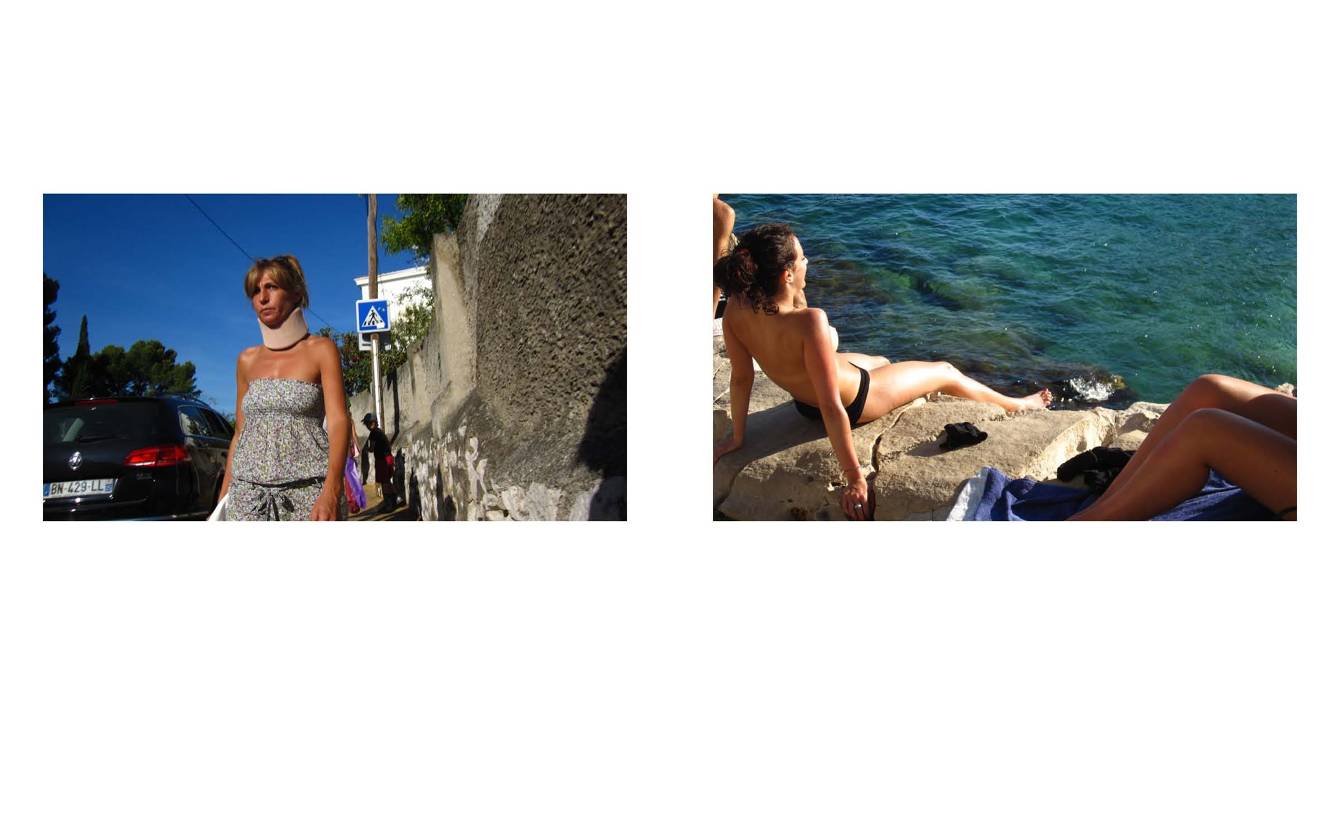

Photography is no longer the capturing of a moment, the photographer secure behind his camera and the world framed just so. It has become a relentless event of seeing and being seen. Which is to say, the photograph does not present us solely with what it sees: Look! An antelope! A poor rural American girl! Yosemite! In this age of the always-on camera—through the looking glass—the photograph presents more than its subject: it presents the very act of seeing these things. The image is at once object and event.

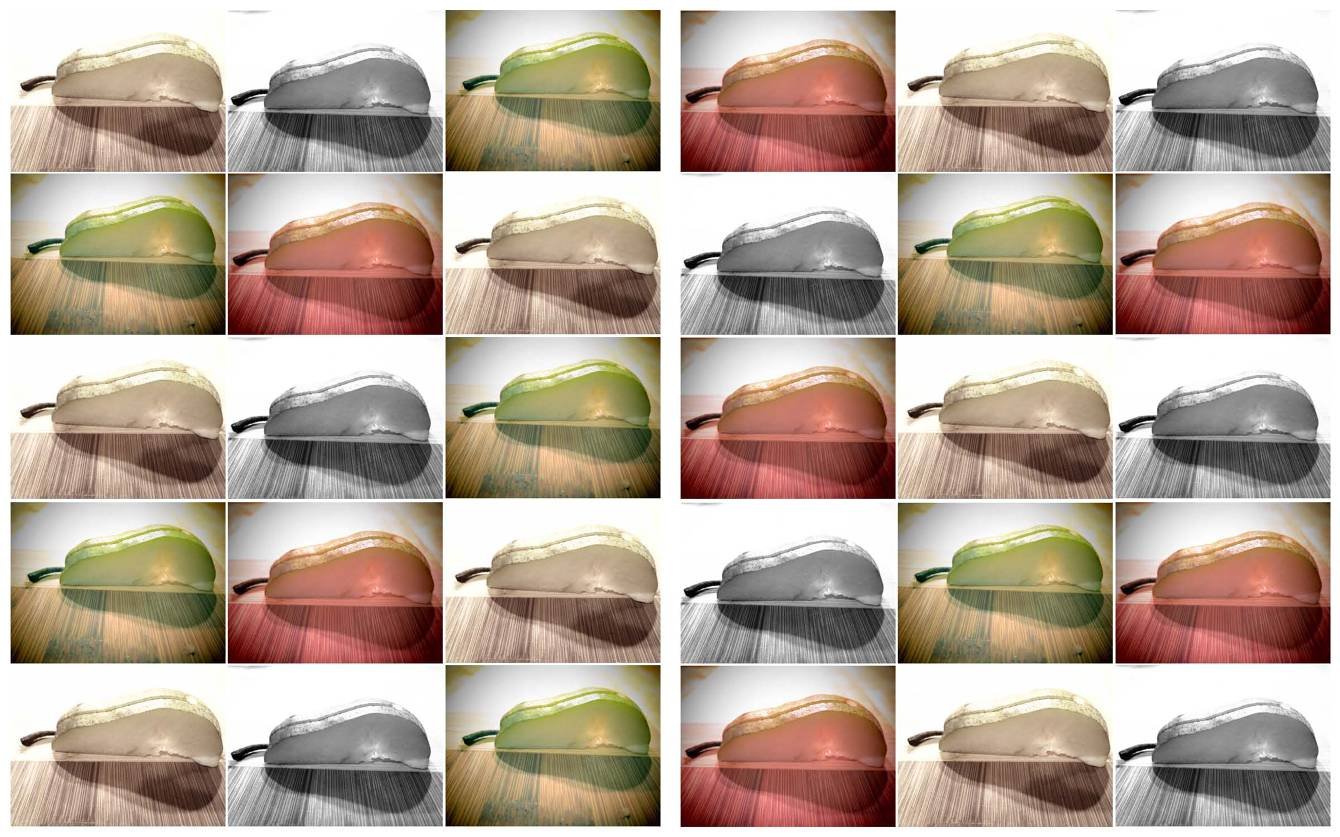

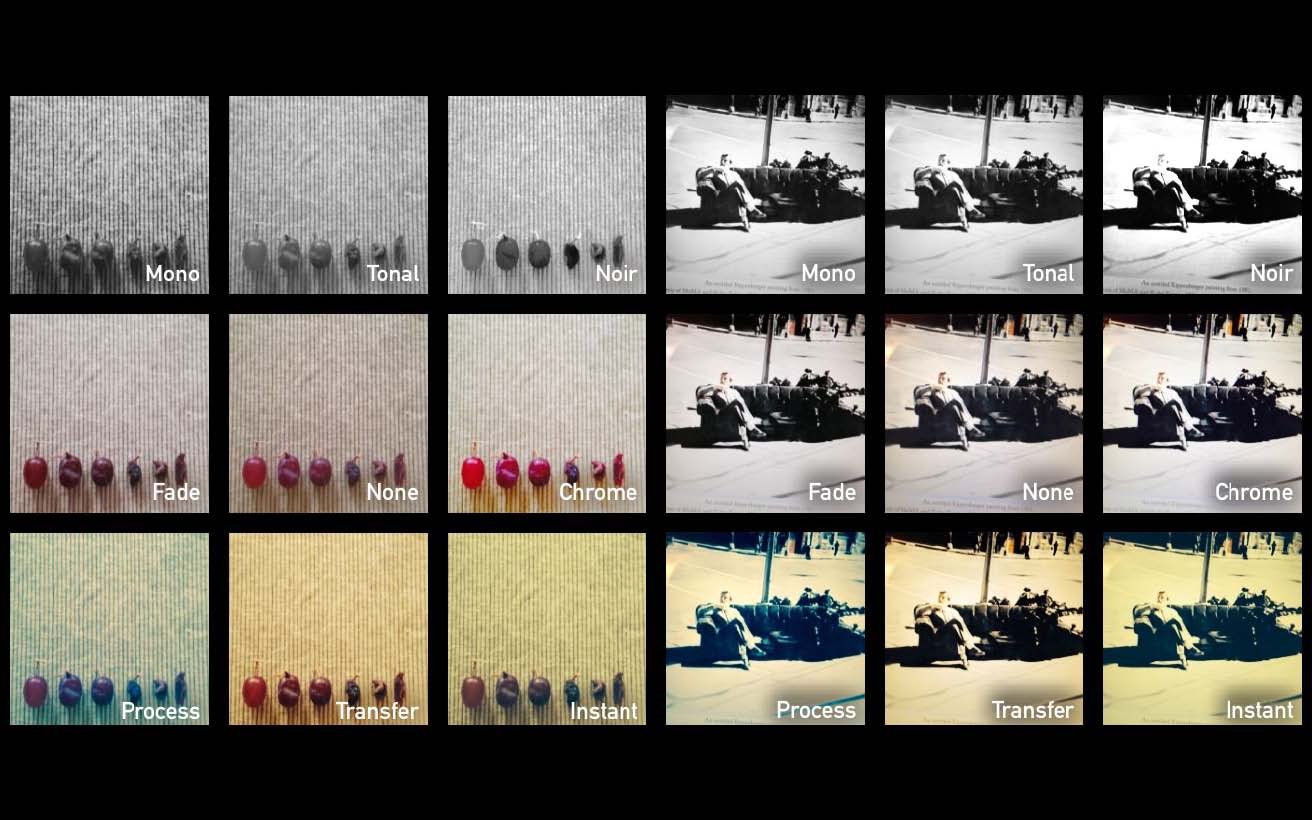

Look at Instagram. We open the app and there, as an image, are the different filters that create the image that we have already taken. We don’t just see the image; we see the tools of the image making along with the archiving and indexing of the image—the views, likes, shares, and comments that follow images around. These are not external to the image; they are constitutive of it. The seeing of the image has become part of the image, folded into the frame. (Movies, too, now come with a making of: to create the film is part of the film.)

This has always been the case. Every photograph has always given us the seeing of the photographer. We don’t just see Yosemite on the postcard: we see Ansel Adams seeing Yosemite. We call this style.

But there’s another seeing we see, as well: the seeing of the image-event. It’s an anonymous, networked seeing, a piece of the world forged then and there, in that moment. The photographic image is not a capturing of a moment—as if it were removed from the world and silently saving this moment for posterity. No, a photograph has always been something created by the very act of imaging, something that wasn’t there before. It’s not a replica. It’s a new thing, quite literally an object, something that inflects light, that takes up the world, that is part of the world.

There’s a New Yorker cartoon that has a woman showing her husband her smart phone: “Look at this image of the thing we’re looking at,” she says. The implication is that this is absurd, that looking at the Golden Gate Bridge is more profound than looking at an image of the Golden Gate Bridge.

But that ancient, Platonic architecture no longer applies. The fact is that image of the Golden Gate Bridge on the smart phone may very well be more beautiful, more profound, than looking directly at the bridge. In any case, the issue of more or less profundity is irrelevant. What’s important is that this image on the smart phone is something—something different, something new, something related to that bridge we’re looking at, but nonetheless different.

The camera never captured what’s there. The camera has always created the image—an image that includes what’s there but is not exhausted by it. The photographic image is not simply a static image of what’s in our minds. I want to say that the photographer is a cut-up artist who takes a mountain, light, sun and gives us this impossibly odd object: a Yosemite image.

To see—to exist—in the new age of the image is always to be participating within this event, always making images, always becoming an image, always seeing seeing, and, in turn, having one’s own seeing seen.

Marc Lafia’s book is situated within this relentless imaging. This is not a book about photography. This is a book of photography, of the image, of the imaging event. It is itself a series of trajectories within the always-on event of imaging that is the seeing-computational network.

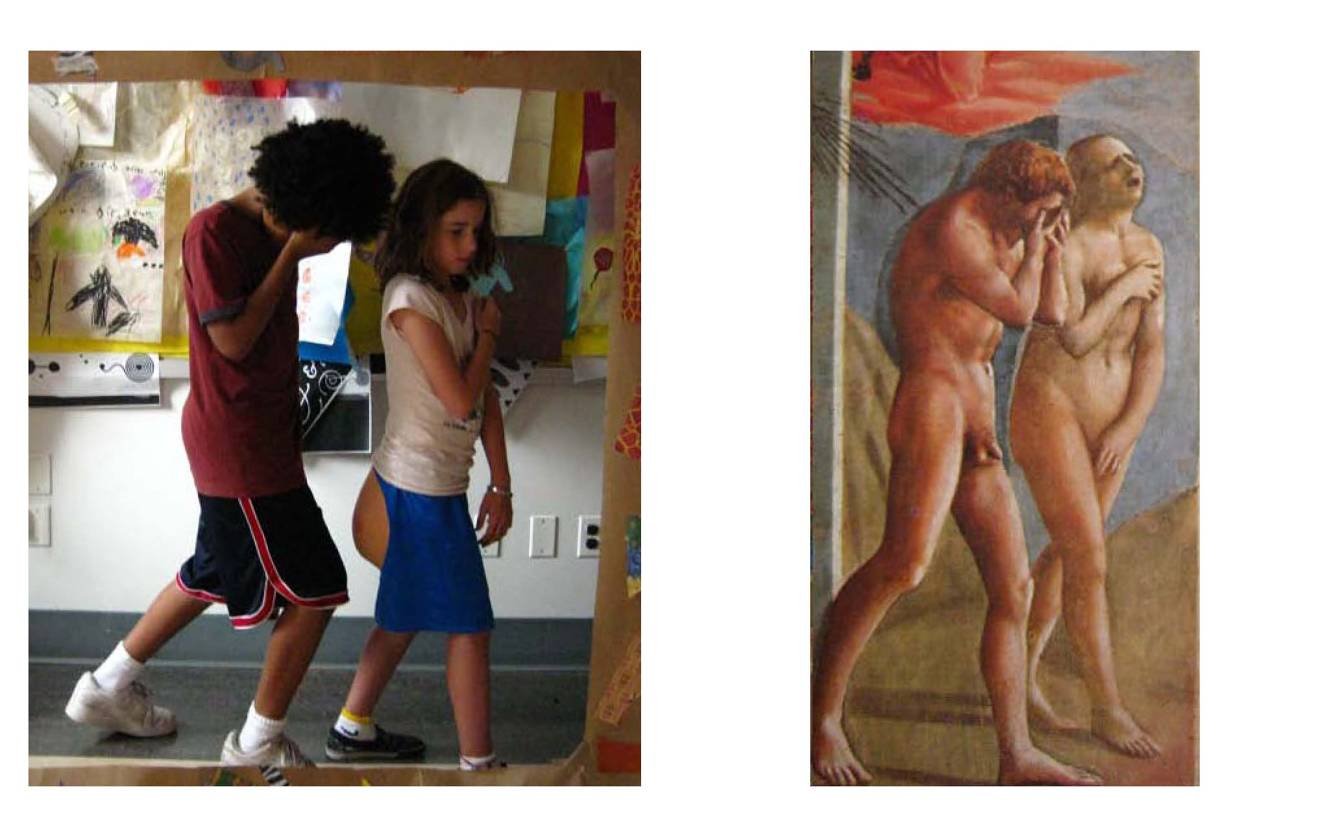

As constitutive and constituent of this teem, Lafia remaps the space of photography by coming at image making first this way, then that. He doesn’t just talk about images—not that there’s anything wrong with that. But in this book, he images. And he writes. What we get are all these different permutations of imaging from within the always-on imaging network. The book is, in every sense, a network effect. And Lafia is an explorer of this strange new landscape.

In his brilliant book The Practice of Everyday Life, Michel de Certeau juxtaposes the map and the tour. With a map, you are outside the space looking down from an impossible vantage point. Maps are amazing at giving us the lay of the land. A tour, meanwhile, is a navigation of the territory from within the territory: Go straight for a bit, and when you see the big red house on your left, turn right.

Well, Lafia’s book simultaneously maps and tours this new landscape of the imaging event. This is not a traditional photography book, precisely because it’s redefining the very territory of photography. I think this is, in fact, the new mode of the photography book: a book that simultaneously creates and questions, proffers and performs.

Lafia takes up the prescribed space of the photography and, by touring the new conditions of imaging, remaps the very space of photography. This is not a condemnation of photography. On the contrary, it’s an opening up, a yawning of possibilities. The photograph is no longer something that is only over there; it now abounds.

This book operates within the space of photography, within the space of the image event. It asks to be read differently than books about photography and differently than photography art books.

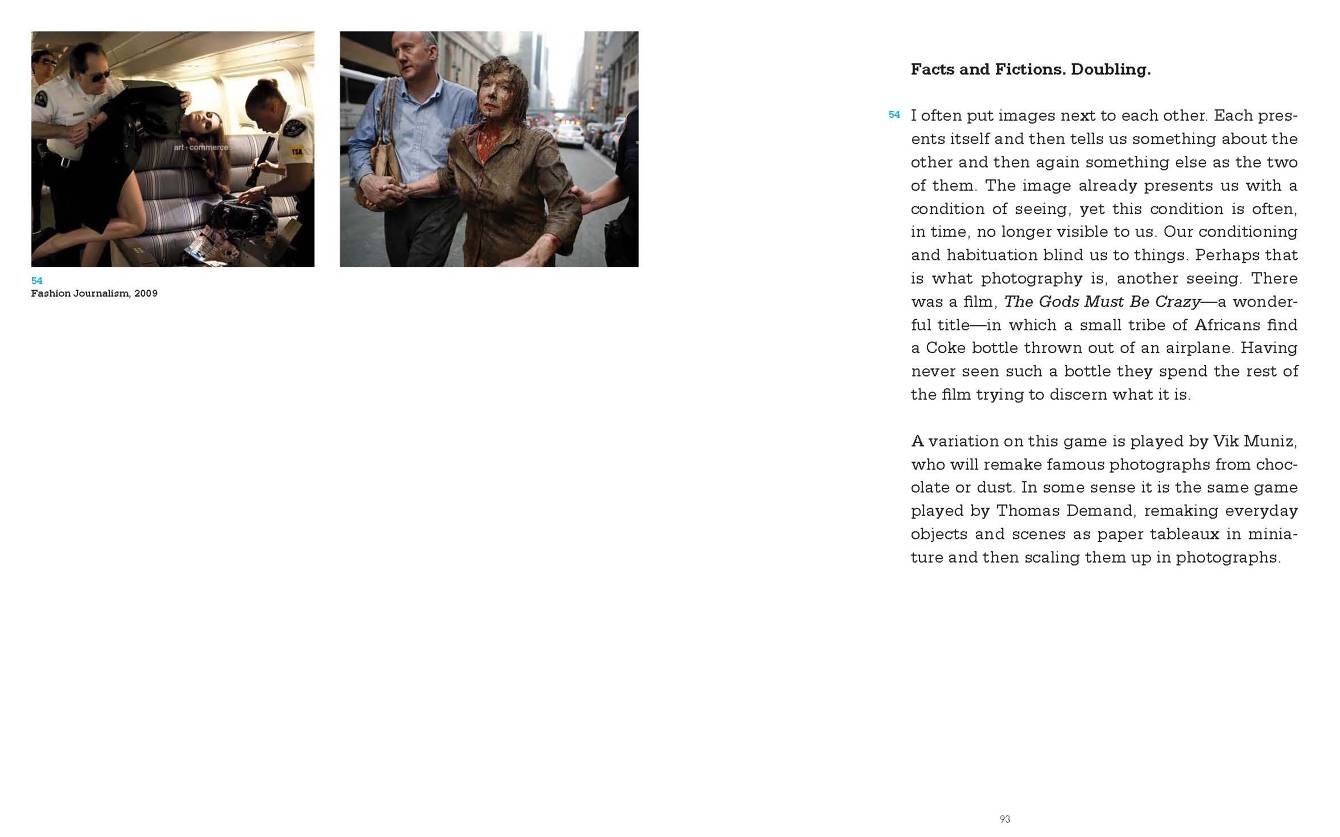

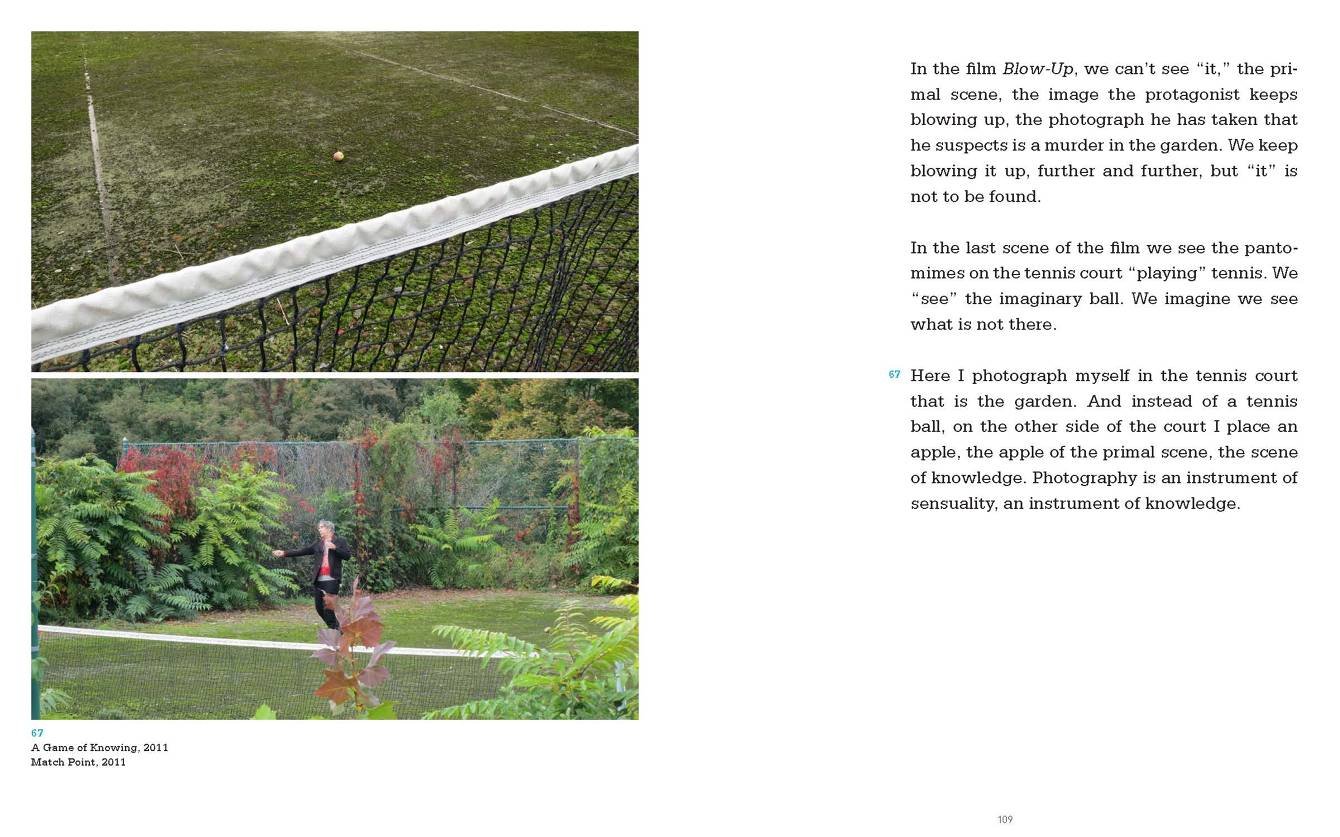

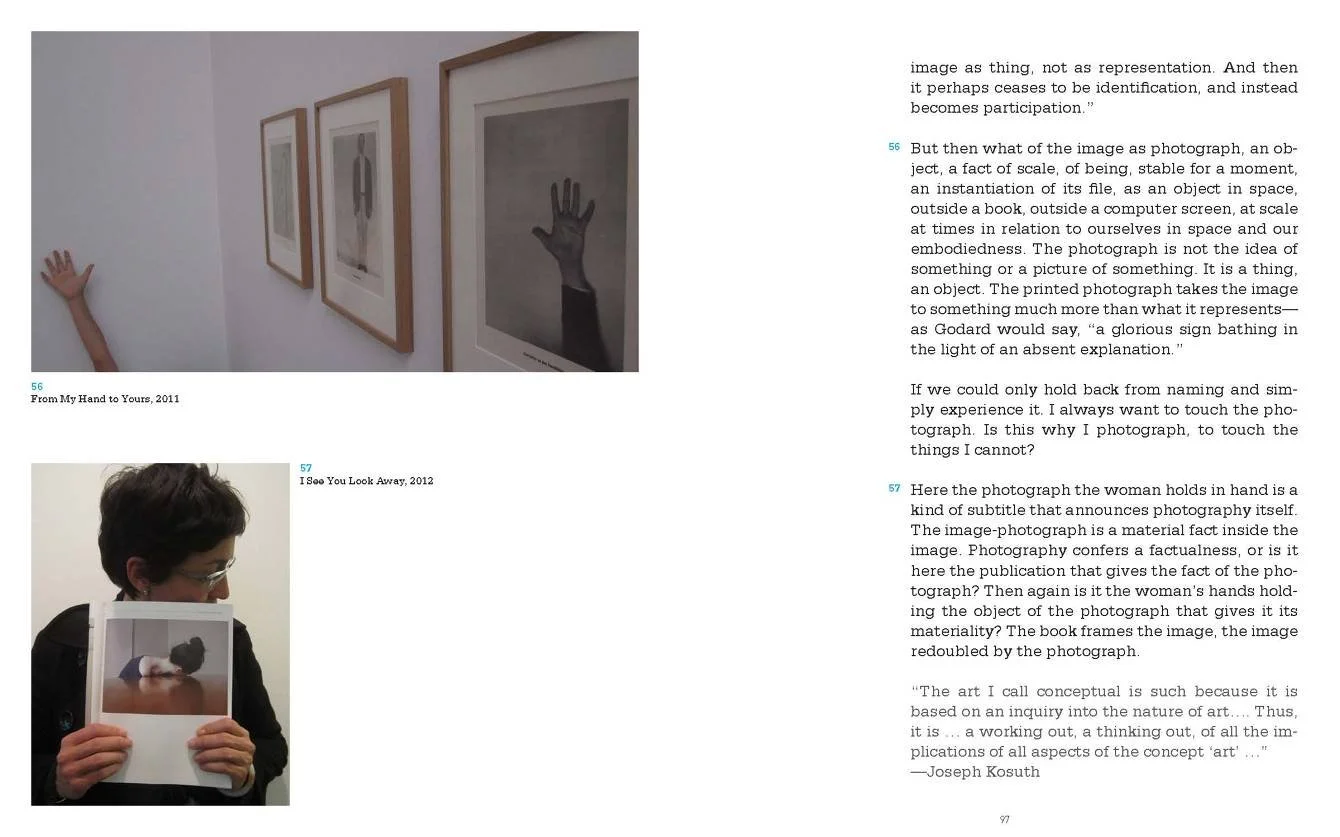

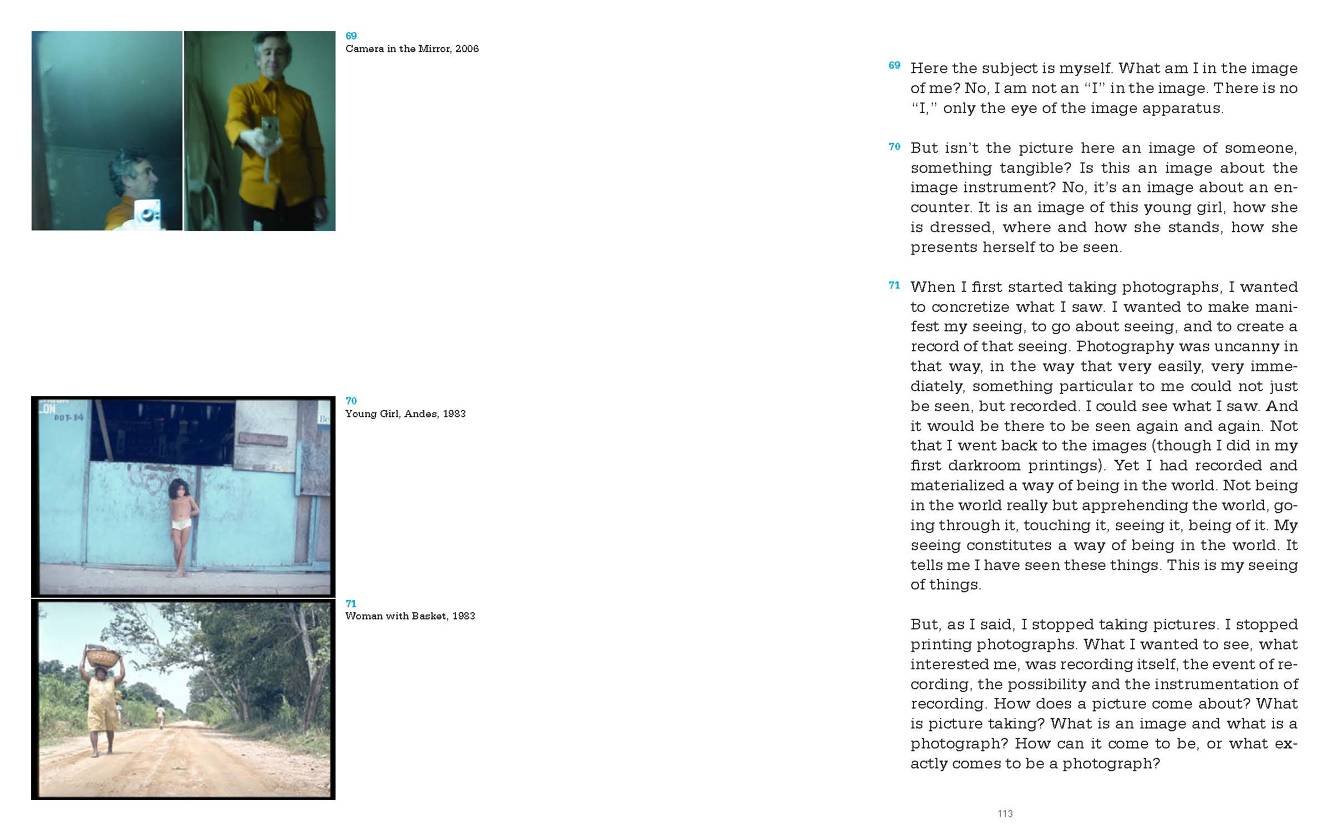

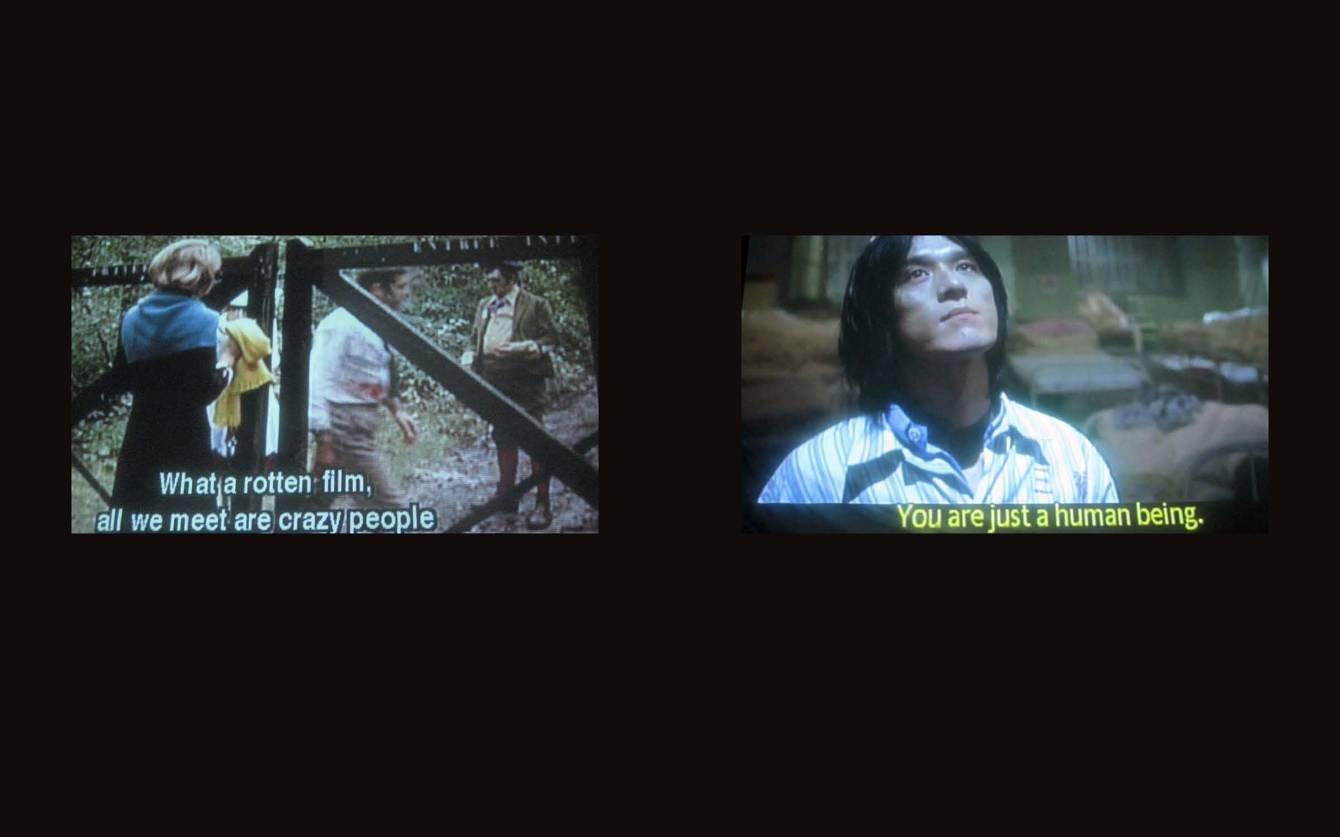

Lafia’s images are not illustrations of his argument. And the text is not explanations of the images. Both text and images are images. Both text and images are arguments. They work in conjunction, mapping and touring, creating a performative cartography of image making today: Photography as an image.